It’s hugely exciting times for college hoops fans, awash in basketball games where they breathlessly wait to see if, oh, the Grand Canyon University Antelopes beat the Iowa Hawkeyes, or if Creighton holds off UCSB, whatever that is. Wait, there is a Grand Canyon University?!

Some $1.5 billion will be bet legally over all the new gambling apps, almost 40 million Americans will fill out those brackets, gallons of newspaper ink will be spilled, and sports analysts will natter on for hours. “Bracketology” will trend on Twitter; coaches’ heads will roll.

Over 19-year-old kids playing hoops. Welcome to March Madness.

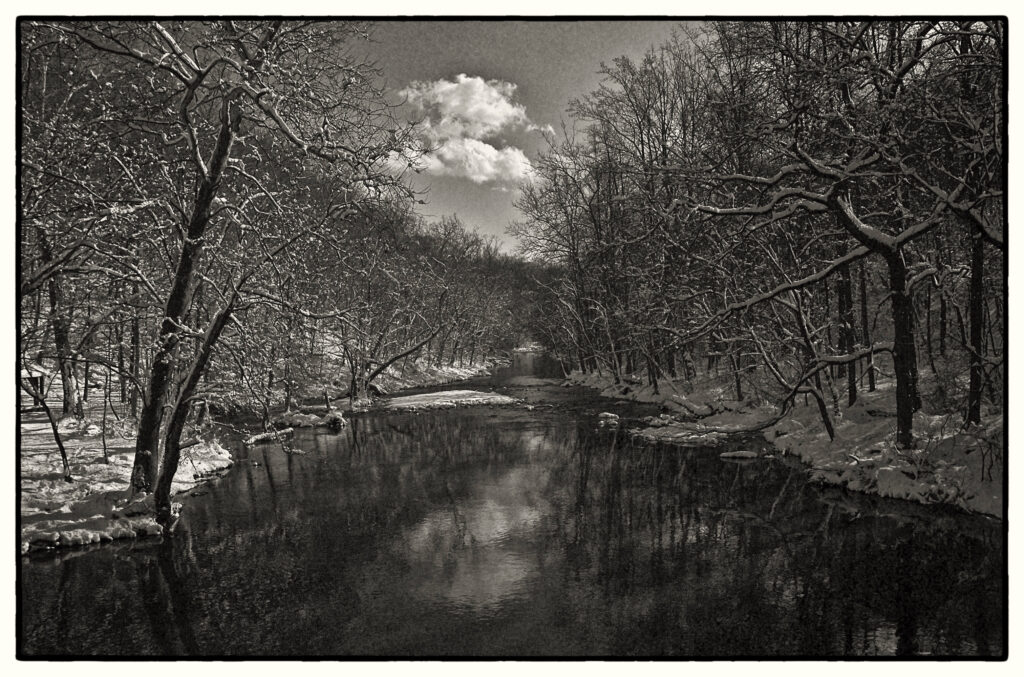

Meanwhile, receiving no fanfare at all, nature in March is simply exploding. Flowers have already begun opening, an elegant parade blooming in an orchestrated sequence begun back in February when skunk cabbages poked through the mud in wet areas, purple mottled hoods protecting a Sputnik-shaped flower. Just this week, the buds of red maples have popped to reveal tiny wind-pollinated flowers, little red spiders dangling from tree branches.

Sure, on our lawns there are snowdrops and crocuses and daffodils and tulips. But our forests will be bursting with ephemeral wildflowers with names as evocative as the flowers are stunning: trout lily, Jack-in-the-pulpit, bloodroot, shooting star, Dutchman’s breeches, Solomon’s seal… With all apologies to the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society (whose show is delayed and outdoors this year—great idea), here’s the real flower show.

Meanwhile, migrating birds are undergoing their own rite of spring, flying through in progression, red-winged blackbirds and phoebes now, ruby-throated hummingbirds later. Waves of woodland warblers—tiny but unbelievably exquisite creatures wearing extraordinary coats of many colors—pass through like clockwork, pine and prairie warblers right now, blackpolls bringing up the rear at season’s end. And they are passing through in their breeding plumage, essentially wearing their Sunday best for us. Just Google “Blackburnian warbler”: is there a prettier animal anywhere?

And while some of these birds are staying for the summer, many are heading to nesting grounds far north of here—think Adirondacks and Canada—only visiting the region for a few days on their journeys north and south. Blink and they’re gone.

Those birds that nest here—cardinals and chickadees, titmice and robins—will be calling their love songs. One of my favorite sounds of spring is the first moment I hear a wood thrush. A cousin of the robin, the thrush’s song is like organ pipes or flute music: it is simply stunning, and stops me in my tracks every spring.

Butterflies soon begin awakening, mourning cloaks first, painted ladies soon, swallowtails in late April, and monarchs, just now leaving Mexico, much later.

Hibernators are crawling out of dens ready to start the new year. Already, painted turtles are basking alongside Fire Pond near the front door of the Schuylkill Center, and American toads will soon be crossing Port Royal Avenue on a dark and stormy night to get to their mating grounds up in the old reservoir across the road. And any day now I expect to see the first groundhog of the season, likely nibbling on roadside grass blades, likely on that high bench of lawn along Hagy’s Mill Road, on the old Water Department land.

That’s the real March madness, that here we are, on the very first days of spring, having survived another wild and wooly winter, having been stuck in lockdown and freeze-down and ice-down, and we’re not betting on the first day a phoebe arrives from the tropics or the first day a mourning cloak butterfly flitters into view. We’re not inviting friends over for a beer to watch our crocuses unfold. We’re not sitting in lawn chairs to admire the red blush of flowers blooming across the maples on our street.

We’re not writing in our brackets which species migrates through first, the yellow-rumped warbler or the great crested flycatcher.

No, we’re debating whether David, the 16th-seeded Drexel Dragons, can slay the Goliath of Illinois, the Big 10 champions and top seed in the Midwest. (OK, here I relent: go Drexel!)

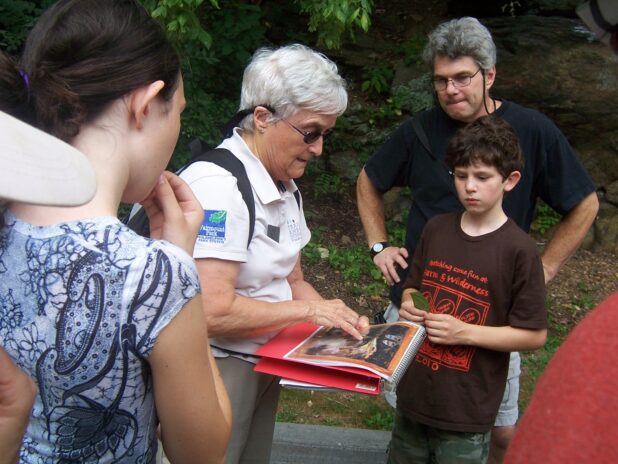

The struggle for me as an environmental educator is that, as a nation, as a culture, we have collectively decided, quietly but definitively, that college basketball matters. Just look at the air time. The ink space. Heck, coaches’ salaries—in many states, athletic coaches are the highest paid state employees.

But nature? Not so much. Sure, it gets a weekly high-quality hour on PBS, but how are those spring wildflowers doing? How are migrating birds faring? How are those monarch butterflies doing, actually on the bubble as a species? Where’s the Nature section of the city newspaper? The culture has spoken, and nature is far, far down our list.

There’s another part of this madness: nature’s elegant springtime succession of flowers blossoming, trees leafing out, and birds migrating is in disarray because the symphony has a new conductor. While climate change is rearranging ancient patterns to an as-yet-unknown effect, the biggest experiment in the history of a planet…

… we’re glued to TV sets arguing over who’s better, Gonzaga or Baylor.

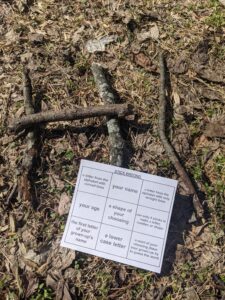

So the real flower show has already started outdoors, in your backyard, in a forest near you. But we’re stuck inside filling out brackets.

That’s just madness.

—Mike Weilbacher, Executive Director