By Claire Morgan, Volunteer Coordinator, and Mike Weilbacher, Executive Director

Throughout our now 50-plus years of educating thousands of people, volunteers have been central to our mission. In fact, we could have accomplished surprisingly little without volunteers. Claire Morgan, our volunteer coordinator, calculates that in the 12-month period ending July 1, volunteers poured 14,000 hours of service into the Center, planting trees, feeding baby birds, measuring water temperatures in streams, hanging gallery exhibitions, even tallying supermarket receipts for dividends.

In this season of giving, we’d like to thank our volunteers for giving us so much.

Like at the wildlife clinic. There, some 70 volunteers in the clinic greatly extend the reach of clinic staff, taking regular weekly shifts cleaning cages, feeding animals, even helping administer medicine. In 2015, about 3,300 wild creatures were brought to the clinic, a record for one year—and without volunteers, rehabilitators Rick Schubert and Michele Wellard would be unable to provide this critical level of service.

Here’s one measure of the importance of clinic volunteers: 10,000 of the hours of volunteer service come from the wildlife clinic alone.

Dan Featherston is one of those volunteers. Helping us for 2½ years now, he “deeply cares” about rehabilitating wild animals, and has a special fondness for pigeons, a bird usually overlooked.

Dan Featherston is one of those volunteers. Helping us for 2½ years now, he “deeply cares” about rehabilitating wild animals, and has a special fondness for pigeons, a bird usually overlooked.

We capped off the recent jubilee year of celebrations with the planting of Jubilee Grove, 200 new trees planted mostly by volunteers and interns. Year round, land stewardship volunteers help stewardship manager Melissa Nase propagate native plants in our greenhouse and nursery. As our native plant sales have been growing in importance, our volunteers are invaluable here, potting plants, caring for the nursery and greenhouse, and even advising customers during the sales as to what plants to use in their own gardens.

Monthly, restoration volunteers join us on the front lines of ecological restoration, removing noxious invasive species that choke out native plants while planting new trees and wildflowers as well.

And then there’s Toad Detour. Unique to Roxborough, every year thousands of toads cross Port Royal Avenue to mate in the reservoir. Instead of getting squashed on the road by passing cars these toads are ushered across by volunteers. This spring, some 1,400 adult toads made the journey through the help of many volunteers, including Scout troops.

The Senior Environment Corps run by Claire leans on a core of wonderful retired adults who, this year, have been monitoring the stream along Wises’ Mill Road to measure the impact of storms on water quality. They share this data with Philadelphia Water and the statewide program Nature Abounds.

We also have a small but dedicated group of volunteers who help us with office skills including data entry, shredding, mailing, organizing, etc. And a new volunteer has just started helping our facilities staff with carpentry and handyman jobs.

Last but not least, an incredible board of 18 volunteer trustees has supported and guided us this year, offering their gifts of time and talent.

Henry Geyer, one of the SEC volunteers, summarizes the experience for many. “Volunteering is my way to say thank you and to give something of myself back to my community. It’s a chance to be with caring people who have your same interests, and hope to make a difference , no matter how slight, in our world. I hope that what little I have contributed will be of some significance.”

Henry, it is. And we are deeply indebted to Henry, and all our extraordinary volunteers.

With a New Year just around the corner, perhaps you’ll make a resolution to give back both to the environment and the community through volunteering.

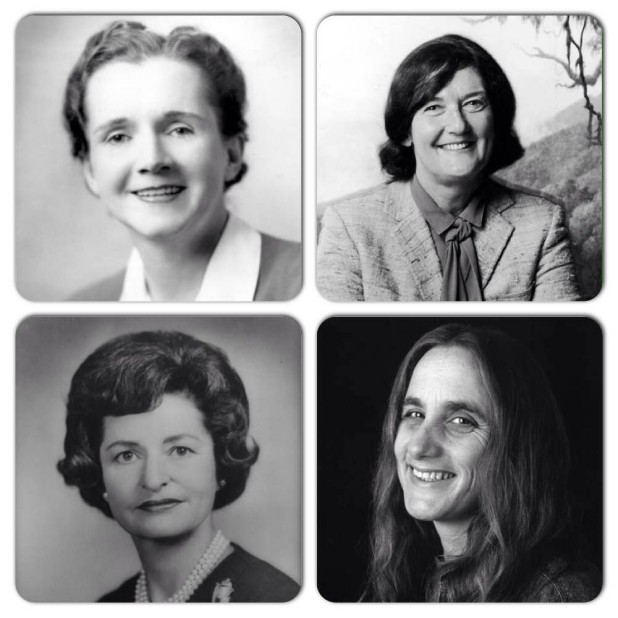

Claudia Johnson, better known as “Lady Bird Johnson,” utilized her position as the First Lady of the United States from 1963 to 1969 to accomplish lasting victories for the environmental movement. Besides playing an active role in the “war on poverty” and the Headstart Program, Lady Bird Johnson worked tirelessly to conduct beautification projects for Washington, D.C, and established the First Lady’s Committee for a More Beautiful Capital. Additionally, she planted bulbs and trees along roadsides to publicize the rapid increase in habitat and species loss during the 1960s. Her efforts culminated in the Highway Beautification Act of 1965, the first major legislative campaign created by a first lady. She delivered her thoughts about a new type of conservation in a lecture to the American Institute of Architects in 1968, which is still very relevant today: “A beautification in my mind is far more than a matter of cosmetics. To me, it describes the whole effort to bring the natural world and the manmade world to harmony,” Lady Bird stated.

Claudia Johnson, better known as “Lady Bird Johnson,” utilized her position as the First Lady of the United States from 1963 to 1969 to accomplish lasting victories for the environmental movement. Besides playing an active role in the “war on poverty” and the Headstart Program, Lady Bird Johnson worked tirelessly to conduct beautification projects for Washington, D.C, and established the First Lady’s Committee for a More Beautiful Capital. Additionally, she planted bulbs and trees along roadsides to publicize the rapid increase in habitat and species loss during the 1960s. Her efforts culminated in the Highway Beautification Act of 1965, the first major legislative campaign created by a first lady. She delivered her thoughts about a new type of conservation in a lecture to the American Institute of Architects in 1968, which is still very relevant today: “A beautification in my mind is far more than a matter of cosmetics. To me, it describes the whole effort to bring the natural world and the manmade world to harmony,” Lady Bird stated. Judi Bari was an environmentalist and feminist who vehemently opposed logging in the ancient redwood forests of Northern California as a principal organizer of the Earth First! campaigns. In order to promote the expansion of natural lands, Bari established her first forest blockade site in 1988 to support the enlargement of the Bureau of Land Management’s Cahto Wilderness Area. In response to loggers’ opposition to the blockades, Earth First!, under Bari’s leadership, launched its Redwood Summer protest. In an effort to reach reconciliation, Bari organized a workshop on the Industrial Workers of the World at an Earth First! event in California. This collaboration between environmentalists and timber workers allowed them to seek solutions to remedy the fast pace at which the timber industry was destroying forests. Although Bari is a controversial figure due to her outspokenness and a mysterious car bombing attempt on her life which led to her being temporarily arrested, Bari’s achievements in preserving the California rainforests are remarkable.

Judi Bari was an environmentalist and feminist who vehemently opposed logging in the ancient redwood forests of Northern California as a principal organizer of the Earth First! campaigns. In order to promote the expansion of natural lands, Bari established her first forest blockade site in 1988 to support the enlargement of the Bureau of Land Management’s Cahto Wilderness Area. In response to loggers’ opposition to the blockades, Earth First!, under Bari’s leadership, launched its Redwood Summer protest. In an effort to reach reconciliation, Bari organized a workshop on the Industrial Workers of the World at an Earth First! event in California. This collaboration between environmentalists and timber workers allowed them to seek solutions to remedy the fast pace at which the timber industry was destroying forests. Although Bari is a controversial figure due to her outspokenness and a mysterious car bombing attempt on her life which led to her being temporarily arrested, Bari’s achievements in preserving the California rainforests are remarkable.

The towpath can also pique your hunger. Depending on how the wind is blowing from Main Street, you may pick up the scent of spicy noodles with chilies, a grilling burger, pulled pork tacos, or the intoxicating smell of fresh-baked bread. From the efforts of numerous community groups who help tend plantings, the towpath is also an ideal place to stop and smell the flowers.

The towpath can also pique your hunger. Depending on how the wind is blowing from Main Street, you may pick up the scent of spicy noodles with chilies, a grilling burger, pulled pork tacos, or the intoxicating smell of fresh-baked bread. From the efforts of numerous community groups who help tend plantings, the towpath is also an ideal place to stop and smell the flowers. About the author:

About the author: