At 1983’s Earthfest, the center’s celebration of Earth Day, participants played with a 6-foot Earthball, one of the many activities at the event. Mike Weilbacher, then a member of the education staff, organized the festival for the center.

By Mike Weilbacher, Executive Director

Wednesday, April 22 marks the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, a watershed moment in American history, and a day that continues to change with the times. While this is not the Earth Day anyone expected, as one billion people from almost 200 countries are NOT, as originally expected, gathering in large protests and celebrations, millions of people worldwide are instead taking to social media to produce an outpouring of hashtags and tweets; 2020 is a decidedly digital Earth Day.

It is worth remembering what happened 50 years ago, because it changed the course of the country.

On April 22, 1970, 20 million Americans–almost one in 10 of us at the time at the time–gathered in what was decidedly a protest, then the largest mass demonstration in American history. People paraded down main streets in gas masks to plead for cleaner air and less smog, buried cars in mock funerals for the internal combustion engine, and held innumerable teach-ins, a phrase borrowed from the antiwar movement, at 2,000 colleges and 10,000 schools across the country.

The day catapulted the environment onto the front pages of newspapers and the lead story for national news shows, and words like “pollution” and “ecology” became quickly embedded in pop culture lingo.

A tidal wave of activism swept through Congress, which soon passed a bipartisan raft of legislation, addressing clean air and water, endangered species, toxic substances, pesticides, surface mining, and much more. They created the Environmental Protection Agency and passed the National Environmental Policy Act that required the creation of environmental impact statements. Republican President Nixon signed all of these bills into law, as his people wanted him to better appeal to younger voters for his 1972 reelection; Nixon and his wife even helped plant an Earth Day tree on the White House lawn in 1970.

For me, few peacetime events in our history have had the legislative track record of Earth Day 1970. And it embedded environmental issues in American politics. “Public opinion polls indicate that a permanent change in national priorities followed Earth Day 1970,” wrote Jack Lewis in a 1990 EPA blog. “When polled in May 1971, 25 percent of the U.S. public declared protecting the environment to be an important goal, a 2500 percent increase over 1969.”

Another child of Earth Day 1970 is the numerous environmental nonprofits that sprang up across the country like mushrooms after a rainstorm, so many tracing their roots to the first Earth Day.

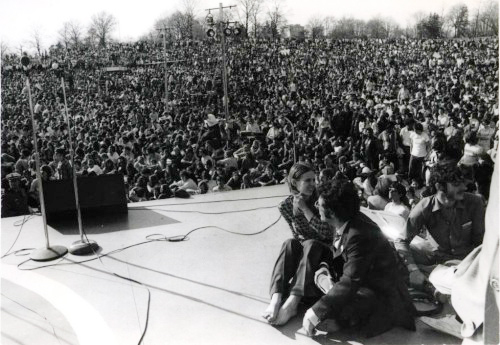

Philadelphia, by the way, rocked the first Earth Day, holding an Earth Week of events that included a huge demonstration at Belmont Plateau (image above) and a reading of a “Declaration of Interdependence” at Independence Hall. The Broadway cast of “Hair” left New York City to sing here, beat poet Allen Ginsberg read his acclaimed “Howl,” Maine Senator Edmund Muskie–then a leading contender for the Democratic nomination for president–headlined at Belmont Plateau; the week’s speakers were a who’s who of American culture at the time: population writer Paul Ehrlich, landscape architect Ian McHarg, science fiction writer Frank Herbert of “Dune” fame, and more. When Walter Cronkite reported about the Earth Day phenomenon on his CBS news show, the image behind the iconic anchor was Philadelphia’s Earth Day logo.

So while COVID-19 has forced us to retreat into a digital Earth Day, radically reducing the visual impact of a billion people protesting around the planet, it is important to acknowledge what that first Earth Day was back in 1970:

A transcendent event that left an indelible mark on the American landscape. It literally changed the course of history–for the better.