A Monarch dries its wings after emerging from its chrysalis in our front garden. (Schuylkill Center, 2013)

By Mike Weilbacher, Executive Director

The new fall season brings a chain of wonderful events: trees turning color, birds migrating south, goldenrod fields bursting in bloom. But one of my favorite fall phenomena is sadly and strangely absent this year.

There are almost no Monarch butterflies afoot these days. All summer, I’ve seen only three at the Schuylkill Center. And my compatriots at other centers like Bowman’s Hill in New Hope and Peace Valley in Doylestown report the same horrific drop.

You know Monarchs, those large orange and black butterflies. Every fall, every Monarch east of the Rocky Mountains begins an extraordinary migration south, one of the strangest in the animal kingdom. All Monarchs, whether hatching here in Roxborough or up in Nova Scotia, fly slowly to a couple of small, secluded mountain valleys not far from Mexico City. Somehow encoded in the pinhead-sized brains of these creatures is a road map to Mexican forests. (West Coast Monarchs, by contrast, head downslope to multiple small locations along the Pacific coast.)

Arriving in Mexico around All Soul’s Day—folk tradition there says these are the returning souls of Aztec warriors—the butterflies cluster in large groups, clinging to each other, coating fir trees with their bodies. Nicknamed the Methuselah generation because they live for many months, this group stays in their mountain cluster until the spring. Then they fly north again, search for the first growths of milkweed plants, (the host plant for their caterpillars), lay their eggs on the milkweed, and die of exhaustion.

Graphic by Journey North

When the next generation matures, it pushes north again—and Monarchs ultimately arrive back in Philadelphia in early summer. Only to head back to Mexico two months later.

Last winter was the worst year on record for the size of the Monarch cluster—their group covered only three acres of forest, down 59% from the previous year, and down 94% from their 1994 high. Think about it: most of North America’s Monarchs clinging to only three acres of trees.

So the drop this year was expected. But it does have biologists wondering about the possibility of losing this utterly unique phenomenon. And all eyes will be on Mexico this year to see how many butterflies return to their winter home.

A Monarch chrysalis hangs from a milkweed stem. (Schuylkill Center, 2013)

Why the drop? Scientists expect many culprits, but highest on the list is the use of Roundup-ready crops through much of the Midwest. Grown to be immune to this herbicide, the plants allow farmers to pour the chemical on fields for weed control, and take out all the milkweed that once supported populations of Monarchs. Pennsylvania’s Monarchs can’t get through the Farm Belt, so few arrive to reproduce here; few in turn migrate back.

At the Schuylkill Center, we’ll watch the butterfly carefully, plant lots of milkweed to support the creature, and report back to you information as researchers discover it. We can’t afford to lose this high-flying beauty from our fields.

Mike Weilbacher, Executive Director, the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education

Learn more at:

“Bring Back the Monarchs,” Monarch Watch: http://monarchwatch.org/bring-back-the-monarchs/campaign/the-details

“Tracking the Causes of Sharp Decline of the Monarch Butterfly,” Yale Environment 360: http://e360.yale.edu/feature/tracking_the_causes_of_sharp__decline_of_the_monarch_butterfly/2634/

US Forest Service, Celebrating Wildflowers: http://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/pollinators/monarchbutterfly/migration/

Toads, singing in afternoon sunlight. A basin in this field fills with water most of the year, creating a nice habitat for toads and other amphibians. Around the field and basin are vines, grasses, and flowering trees.

Toads, singing in afternoon sunlight. A basin in this field fills with water most of the year, creating a nice habitat for toads and other amphibians. Around the field and basin are vines, grasses, and flowering trees.

Melissa Nase, Manager of Land Stewardship, transplants tiny Rudbeckia, black-eyed Susan seedlings in the Native Plant Nursery. These seedlings were grown from seeds collected here at the Schuylkill Center.

Melissa Nase, Manager of Land Stewardship, transplants tiny Rudbeckia, black-eyed Susan seedlings in the Native Plant Nursery. These seedlings were grown from seeds collected here at the Schuylkill Center.

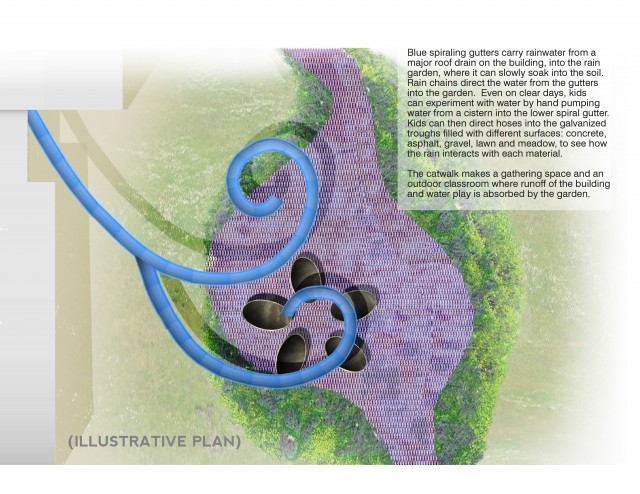

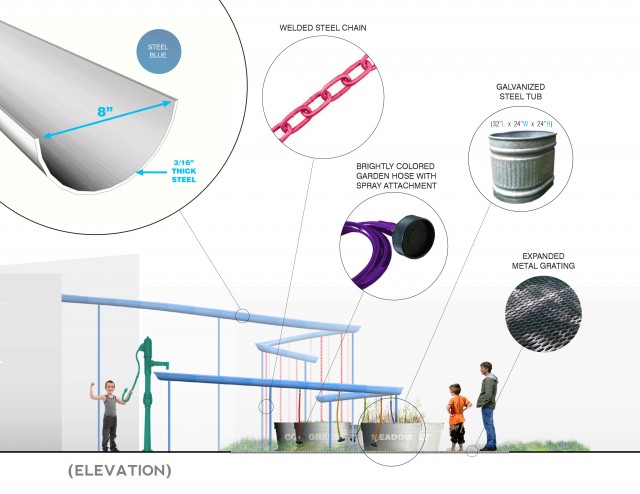

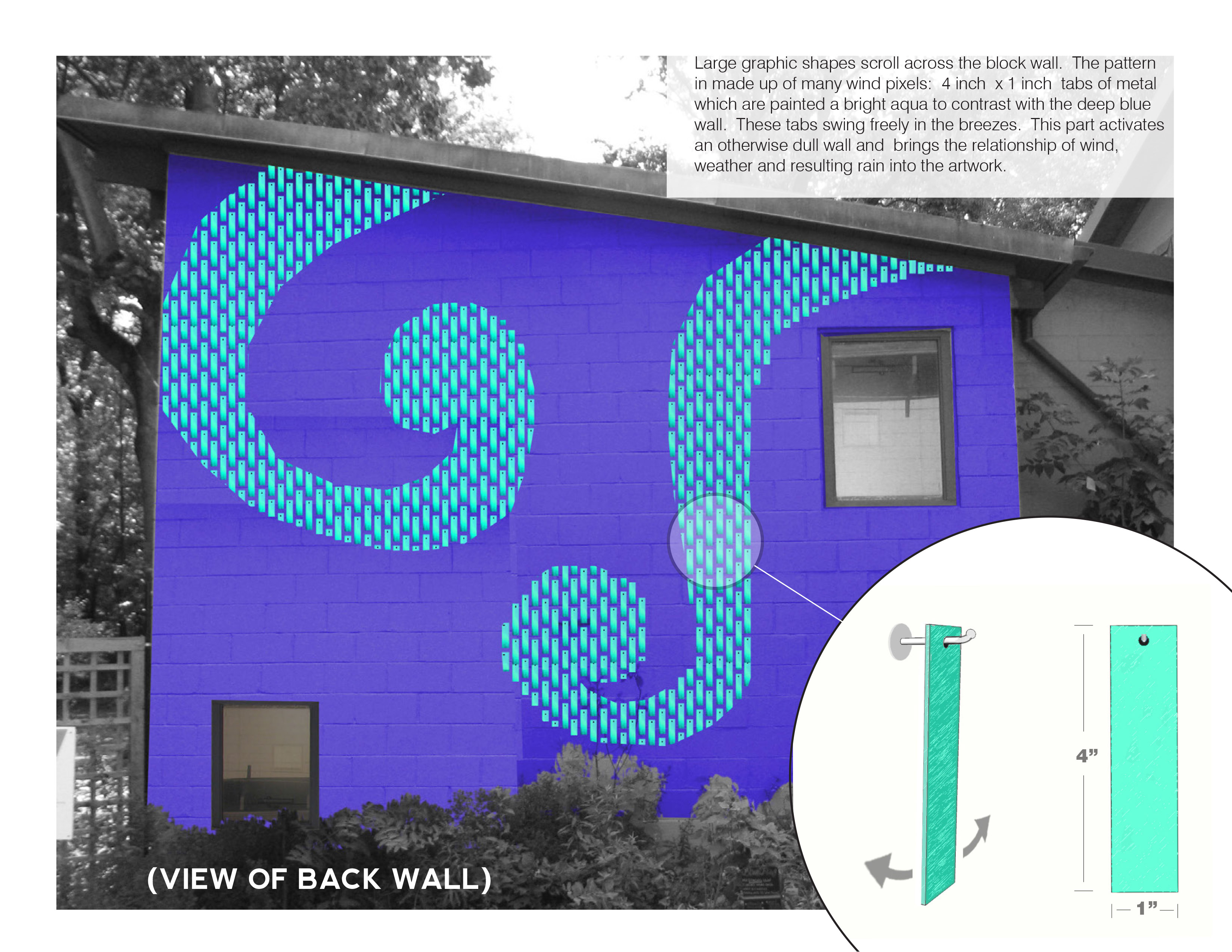

Rain is usually given a long narrow space to inhabit: gutters, downspouts, underground pipes. People can walk practically anywhere in a building and on the surrounding landscape. What if this paradigm got turned on its head? Give people a more narrow path of movement around a site while rain gets plenty of space to spread out and linger? How would our built environments change? And how would it change our relationship to rain?As an eco-artist, I want art to be an advocate of rain. Art is good at giving meaning to the leftover or abandoned aspects of the world—and rain is one of those abandoned elements. Though a

Rain is usually given a long narrow space to inhabit: gutters, downspouts, underground pipes. People can walk practically anywhere in a building and on the surrounding landscape. What if this paradigm got turned on its head? Give people a more narrow path of movement around a site while rain gets plenty of space to spread out and linger? How would our built environments change? And how would it change our relationship to rain?As an eco-artist, I want art to be an advocate of rain. Art is good at giving meaning to the leftover or abandoned aspects of the world—and rain is one of those abandoned elements. Though a