Later today at 5:24 pm, a vertical shaft of sunlight grazes the equator: it’s the first moment of spring. Greetings of the season, usually worth celebrating. Not this year.

For our weirdly snowless winter has already yielded an eerily early spring. While perhaps you’ve already noticed too-early crocuses, daffodils, and even dandelions, our forests have fast-forwarded into spring.

At the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education in Roxborough, painted turtles started sunbathing on pond edges in February. At the Briar Bush Nature Center in Abington, red-backed salamanders were spotted out of their burrows at the end of February. Skunk cabbage popped up in late December, two months ahead of schedule, at the Silver Lake Nature Center in Bristol, and garter snakes were seen basking in January. January!

Spring was once an elegantly choreographed parade of extraordinary events that evolved over millennia. Birds migrate north to take up their nesting sites just as trees leaf out and insects awaken from hibernation. Frogs and toads hustle to ponds and wetlands for their mating rituals, spring peepers early, bullfrogs much later. Among birds, Eastern phoebes swoop in early, their flicking tails a welcome sight; blackpoll warblers with their squeaky-wheel song pass through much, much later.

But climate change has upended this parade; the orchestration is completely out of whack. Spring may have been broken by climate change.

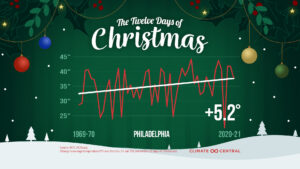

The conventional wisdom among climate scientists is that, with our supercharged climate, spring has been moving up about 2.5 days every decade. The government’s National Phenology Network reports that Philly’s spring is 20 days early this year, which is troublesome by itself but reads to me frankly like a conservative estimate. Still, this is one of the earliest springs on record.

Yes, there were always years with randomly warm Februarys and freakish April snowstorms, but nature always had the capacity to withstand these occasional anomalies. With snowless winters and too-early springs, the parade’s choreography dissolves with many still-unknown impacts on the species that share Pennsylvania forests with us.

Plants, for example, may open before their pollinators awaken or arrive, and unpollinated flowers won’t produce the seeds that they – and many seed-eating animals – require. When migrating birds arrive to begin nesting, they desperately need to find huge numbers of insects to stuff into the gaping maws of their nestlings; if they cannot find the insects, or if caterpillars have finished their larval growth and are already butterflies and moths, the parent birds will struggle to raise their young. At the Schuylkill Center, mangy foxes have been seen this year, the mange caused by mites that are typically killed by winter’s cold. Not this year, and foxes are struggling.

On the Delaware Bay, for millions of years horseshoe crabs have hauled themselves onto beaches around Mother’s Day to lay billions of green BB-sized eggs in the surf. At the exact same moment, a rusty-bellied shorebird called the red knot arrives exhausted, in the middle of one of the longest migrations of all, from the tip of South America up to the Arctic Circle. Famished, these fat-rich eggs give the birds the EXACT energy boost they need to finish their journey north – and they gobble them fiercely, as do so many other shorebirds. If this elegant partnership gets out of whack, the already-scarce knots will simply not survive the epic trip, and we will lose a remarkable species.

Sixty years ago, acclaimed writer Rachel Carson worried about a “silent spring,” as her groundbreaking book of that title warned about the dangers of DDT. Happily, our springs aren’t silent.

But they are shaken – and breaking – from climate change.

Writer-naturalist Mike Weilbacher has just published “Wild Philly: Explore the Amazing Nature in and Around Philadelphia,” and directs the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education.