Why did hundreds of toads cross the road on a rainy Wednesday night?

As ever, to get to the other side; migration season is in full swing.

Every year in late March and early April, the amphibians wake from hibernation to mate and lay eggs, and they begin the treacherous journey from Schuylkill Center forests to the Roxborough reservoirs and back. The most treacherous part? Crossing Port Royal Avenue, often during evening rush hour. The toads mostly move in dusk and darkness to avoid animal predators—but that method doesn’t work so well for cars.

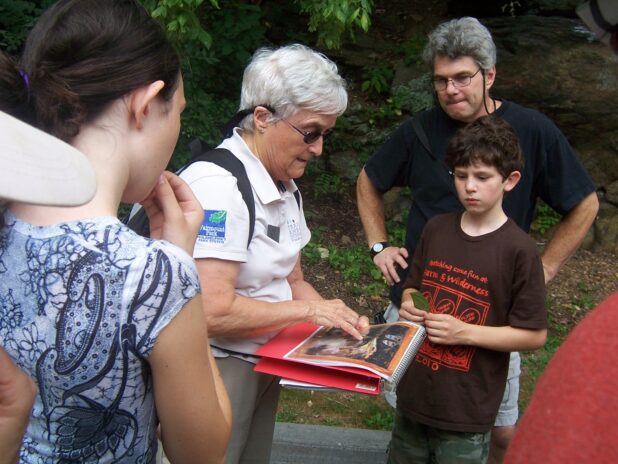

Sixteen years ago, a group of volunteers set out to give these toads safe passage across the road, by erecting barricades and redirecting traffic around Port Royal Avenue. The Schuylkill Center took over this program three years in and has been running it ever since, under the affectionate name “Toad Detour.” It’s the largest volunteer operation we have, and folks come back year after year to participate.

“It’s a great opportunity to have fun, learn more about amphibians and save the future, so to speak,” says Paulina Le, the Volunteer Coordinator for the Schuylkill Center. “Toad Detour makes people feel like they are a part of something bigger than themselves.” They come for nights full of the camaraderie of shared purpose, and for quiet, excited observation of the toads’ epic undertaking. As volunteer Sandy Brubaker describes it, she “Really enjoy[s] hearing them first, usually leaves rustling on the side of the road, and then seeing that first one!” Longtime volunteer leader Ed Wickham agrees, saying “I never tire seeing and hearing the toads, frogs and toadlets every year. They are my first sign of spring like the cherry blossoms or snow geese.”

How do they know when toads may make an appearance? First the weather has to be warm enough—the ground temperature needs to be consistently around 55°F—and ideally a bit wet or rainy. But the most telling sign: the male toads will begin their mating call, a high pitched trill that sounds through the night. This is a cue for volunteers to take to the streets.

A male and female toad in “amplexus,” or their mating position, as they cross the road. Photo by Kevin Kissling

On the evening of Wednesday, March 31, no fewer than 543 live toads crossed the road, assiduously counted by our volunteers. (A few pickerel frogs also showed up to the party.) Counting the toads helps us track the size and health of local toad populations—which in turn indicates the health of the entire habitat. The numbers also make an online tool created by a long-time volunteer, the “Toad Predictor,” more accurate. While we don’t yet submit the numbers formally to a database as you might for migrating birds or butterflies, documenting the toads supports the necessity for road barriers.

And this is only part one of the journey: The eggs laid in the reservoirs will hatch three to 12 days later, and once the tadpoles mature into toadlets (tiny toads the size of your fingernail), they cross the road once more to get back to their terrestrial home territory. “They have tough lives,” Wickham says. “Only a very small percent of toads born become adults. To have a big female toad survive against all odds then be killed by a car is tragic.” So he has one final plea for you: “Please volunteer. Please volunteer often. Volunteers that show up many times a year every year are so valuable. They rescue more toads than anyone else.”

Sometimes volunteers use buckets to more effectively and safely transport toads across the street, and sometimes they use them to protect toads hopping their way over outside of the barrier zone. Photo by Colleen DiCola

As more and more nature centers throughout the country take up similar toad and amphibian detour operations, some also engineer special wildlife bridges and tunnels. As Paulina says, “Many folks are adapting the principle of living with the environment, not against it.” The toads, after all, “have been here longer than humans have”—and they’re certainly not going to let a road get in their way.

—Emily Sorensen

Further resources:

Sign up to be a Toad Detour volunteer

What does the toad say? By Clare Morgan

Watch Doug Wechsler’s Thursday Night L!VE talk on the life of a toad

Read a review of Wechsler’s book The Hidden Life of a Toad (available in our Nature Gift Shop)

One of the feel-good stories on the environmental scene is the rewilding of large cities like Philadelphia, where suddenly peregrine falcons nest in church steeples and on Delaware River bridges, bald eagles pull large fish out of the Schuylkill River, and coyotes amble down Domino Lane.

One of the feel-good stories on the environmental scene is the rewilding of large cities like Philadelphia, where suddenly peregrine falcons nest in church steeples and on Delaware River bridges, bald eagles pull large fish out of the Schuylkill River, and coyotes amble down Domino Lane.