By Christina Catanese, Director of Environmental Art

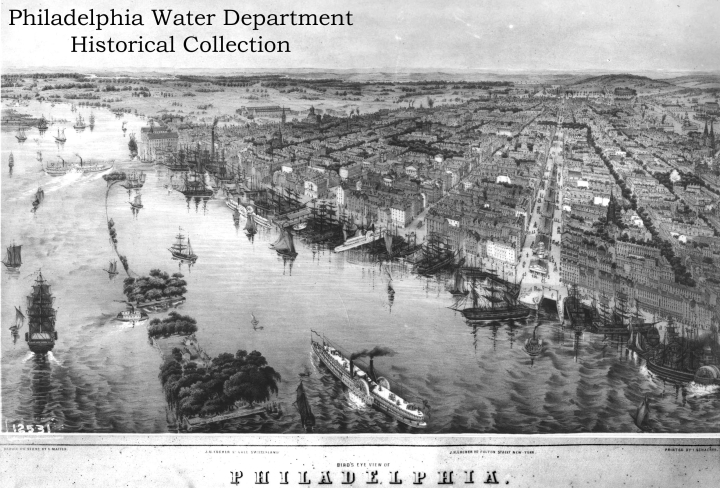

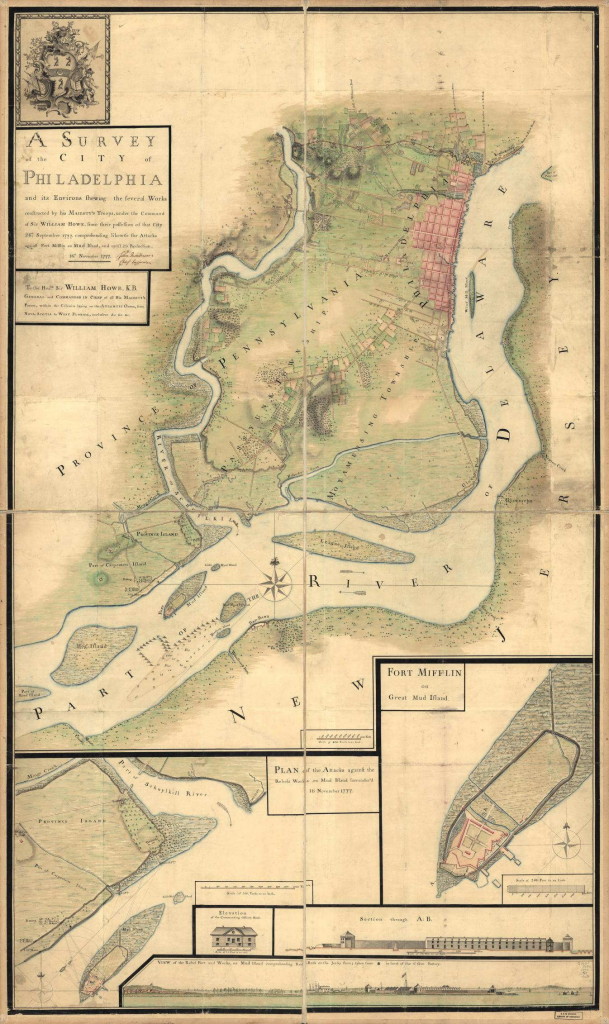

Often, when I fly into Philadelphia International Airport, I imagine what a bird’s eye view of the area must have looked like back before Philadelphia became the bustling metropolis it is today. If I squint just the right way, I can almost see how the flat expanse of skyscrapers and rowhomes transforms to green, how South Philly and even the airport itself melt into the freshwater tidal wetlands that were once in their place (the last remnant of which is still visible at the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge).

Many cities are built on what used to be wetlands – flat, open, marshy areas that were easy to fill and build or farm on. Wetlands were traded for dikes and dredged shipping channels, especially along the Delaware waterfront. But we have often done this at our own peril – what seemed to early settlers to be wastelands not only teem with life, but protect us in ways we don’t always recognize. Wetlands serve as a critical line of defense from flooding, and act as filters for pollution. In many ways, wetlands are an armor of resilience against major change and catastrophe.

Many cities are built on what used to be wetlands – flat, open, marshy areas that were easy to fill and build or farm on. Wetlands were traded for dikes and dredged shipping channels, especially along the Delaware waterfront. But we have often done this at our own peril – what seemed to early settlers to be wastelands not only teem with life, but protect us in ways we don’t always recognize. Wetlands serve as a critical line of defense from flooding, and act as filters for pollution. In many ways, wetlands are an armor of resilience against major change and catastrophe.

Hurricane Sandy brought this into very clear focus, with one rare bright spot being the role played by coastal wetlands in softening to some extent the blows from storm surges and waves that pummeled the east coast. In anticipation of increasingly severe storms as the climate changes, many cities are restoring the wetlands at their edges and turning formerly industrial waterfronts into vibrant public spaces, bringing nature back into the city where we once ushered it out. When I think of nature in the city, I think of the natural and constructed systems that interact to form the background, and at times the foreground, of every moment of our lived urban experience.

Hurricane Sandy brought this into very clear focus, with one rare bright spot being the role played by coastal wetlands in softening to some extent the blows from storm surges and waves that pummeled the east coast. In anticipation of increasingly severe storms as the climate changes, many cities are restoring the wetlands at their edges and turning formerly industrial waterfronts into vibrant public spaces, bringing nature back into the city where we once ushered it out. When I think of nature in the city, I think of the natural and constructed systems that interact to form the background, and at times the foreground, of every moment of our lived urban experience.

If wetlands are our armor, artists like Mary Mattingly are the foremost division in our environmental army. Environmental art is, in its nature, always exploring the far edge of both art and the environmental movement, and as climate change becomes a part of daily reality, environmental art is evolving to respond.

In August 2014, as part of the Philadelphia Fringe Festival, Mattingly launched WetLand on the Delaware River, just outside the Independence Seaport Museum. WetLand is a mobile, sculptural habitat and public space constructed to explore resource interdependency and climate change in urban centers. A floating sculpture-plus-residence, it resembles a partially submerged building, and integrates natural living systems into an urban space. WetLand’s ecosystem contains rainwater collection and purification, greywater filtration, dry compost systems, outdoor vegetable gardens, wetlands, and hydroponic gardens. Walking aboard WetLand this summer, I was struck at how Mary brought pieces of nature into the city, inspiring new ways of being in a changing world.

In August 2014, as part of the Philadelphia Fringe Festival, Mattingly launched WetLand on the Delaware River, just outside the Independence Seaport Museum. WetLand is a mobile, sculptural habitat and public space constructed to explore resource interdependency and climate change in urban centers. A floating sculpture-plus-residence, it resembles a partially submerged building, and integrates natural living systems into an urban space. WetLand’s ecosystem contains rainwater collection and purification, greywater filtration, dry compost systems, outdoor vegetable gardens, wetlands, and hydroponic gardens. Walking aboard WetLand this summer, I was struck at how Mary brought pieces of nature into the city, inspiring new ways of being in a changing world.

Mattingly will give this year’s fourth annual Richard L. James Lecture at the Schuylkill Center on January 28th, Environmental Art for a Changing Planet. An interdisciplinary panel will reflect on this work in the context of the history of environmental art, its current state, and what the future of the genre (and our world) may look like. A gallery show (also opening that evening with a reception after the lecture and discussion) gives an inside look at WetLand. It’s a fitting way to kick off our celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Schuylkill Center in 2015, which happens also to be the 15th anniversary of our pioneering environmental art program. Dick James, as many remember, was the founding director of the Center, a fixture in the community for more than 30 years.

Mattingly herself has written, “Art is integral to imagining new worlds” – and, I would argue, to building them.