The New Year is a great time to go for a walk in a natural area near you– the Wissahickon, Andorra Meadow, the Schuylkill Center, anywhere. The walk likely helps you meet one of your resolutions– yes, get those 10,000 steps!– while being outside allows you to sidestep that accursed virus that’s been, sorry, plaguing us unmercifully for two years now. And being outdoors allows you to lower your stress levels, as time in nature is restorative and calming. In 2022, make sure to get plenty of outdoor time.

And when you do, Christmas fern will likely be along for the walk.

One of the most common plants in Wild Philadelphia, Christmas fern is also one of the easiest ferns to spot– and know by name. Its fronds are evergreen, so on a Christmas morning walk through a forest, you’ll see its green fronds along the forest floor. Few other plants besides evergreens, rhododendrons, and hollies are still green at this time of year. And if you check out a leaflet– go ahead, look closely– it has a cute little bulge on the bottom, looking, without stretching the imagination too far, something like a Christmas stocking hanging from a fireplace.

Hello, Christmas fern, your introduction to the world of ferns. While there are hundreds of fern species locally, including many that are devilishly hard to key out to species, Christmas fern offers, appropriately, a present of sorts: it is easily knowable as one of the few green things growing along the forest floor right now. I’ve led scores of walks where people want to know the name of this or that fern, and I have to confess that it is likely a member of the giant wood fern clan, a notoriously hard knot to unravel. And lowly ferns just don’t get the love they deserve, as they are lower plants, ones without any flowers whatsoever.

But ferns are important, and are a wonderful story. The first ferns appeared on our planet some 360 million years ago, 100 million years BEFORE the earliest dinosaurs. Ferns are so ancient they predate flowers: Stegosaurus might have munched on ferns, but it never ate a flower. And in Pennsylvania’s geologic history, ferns dominated the dense primeval swamps that were buried underground, the peat slowly cooking to form coal, our state’s iconic fossil fuel.

Our state’s economy is built on the lowly fern.

The Christmas fern’s genus, Polystichum, is very successful, as it is found worldwide, its cousins growing across the entire planet. One reason Christmas fern is so common in local forests is that deer do not seek them out, a great advantage in forests typically overbrowsed by deer. (But fern fiddleheads are all edible, so perhaps consider sauteing some in the spring.)

Ferns create spores, not seeds, and most do so on fertile fronds, specialized fronds carrying structures holding the spores, often on the underside of the frond. In the Christmas fern, sterile fronds typically encircle taller fertile ones, which are also held more erect. Spores tend to be created between June and October when the conditions are right. The fertile leaflets are at the tops of their fronds– check out frond undersides during summer and fall, looking for brown spots, the sacs that create spores. In the winter, those fertile fronds die away, leaving their sterile evergreen sisters.

While Christmas fern can form colonies, it more typically grows singly or in twos or threes, the foot-long fronds appearing rather tough and leathery. In the winter, it is not unusual to find flattened fronds on the forest floor, squashed from a snowfall, but doggedly remaining green.

So do get your outdoor steps in this New Year as part of your self-care plan, and do introduce yourself to Christmas fern, unwrapping its gifts as you walk.

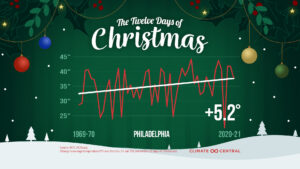

Climate Watch. New for 2022, this column will end every week with a special update on the unfolding climate crisis, a situation I have long labeled the New Abnormal. Last week, wildfires swept through the Denver suburbs. Fueled by high winds (110 miles per hour) and an extremely dry climate, as of Friday of last week almost 2,000 acres and 500 homes burned while tens of thousands of Coloradans were evacuated– on New Year’s Eve. Those numbers will likely have climbed by the time you read this.

When wildfires flare in the ski-resort capital of the country in the winter, you are unquestionably seeing the impact of climate change.

By: Mike Weilbacher, Executive Director