Postponed for a year, we’re excited to celebrate Earth Day 50+1 years in 2021. But as we start into new creative endeavors, we want to take a moment to look back at last year’s exhibition Ecotactical: Earth Day at 50. On display from September through December 2020, Ecotactical explored how the celebration of Earth Day has changed over time, and asked what the significance of the holiday means five decades after its conception. The exhibition featured works from various artists installed onsite in our gallery and along our trails. Each artist responded in a unique way, giving new perspectives into what Earth Day means to them personally, and to the world. But creating and presenting an exhibition in the midst of a pandemic came with challenges, as well as with new possibilities. We adapted to new timelines, new restrictions and new technologies, but in the end, the message is still clear: Earth Day remains an integral part of the ongoing fight for ecological change and environment justice. We look forward to carrying with us the energy and strength into 2021 that our artists and our team showed in making Ecotactical possible.

With a new year comes new energy behind this movement. We asked the Exhibition Coordinator and the artists to reflect on a series of questions, prompting them to consider the meaning of Earth Day and its relation to the things that have been happening in the world since the inception of the show. Below we share some of their responses and thoughts on this show.

Asking our Exhibition Coordinator, Liz Jelsomine: While working with the artists and for the Schuylkill Center’s staff, how has your view on the world and Earth Day specifically has changed with the pandemic?

Winter 2019/20 was an exciting time at the Schuylkill Center. The 50th anniversary of Earth Day was approaching, and the possibilities of what that meant to our organization and for the future of our world was inspiring. To commemorate, we were gearing up for our annual Earth Day celebration, Naturepalooza, and the Environmental Art Department was planning the final details for our Earth Day themed show, Ecotactical: Earth Day at 50, due to open just before Earth Day on April 16.

Then, suddenly, the world erupted with news of a dangerous and very contagious disease, so devastating that society as we knew it would be put to a halt for the unforeseeable future. We know the disease all too well now as Covid-19. Business closures, job insecurity, isolation from others, and personal loss, were just a few of the hardships society was faced with. The Schuylkill Center made the difficult decision to cancel Naturepalooza. Ultimately, our center, along with many other businesses, had to temporarily close our doors. This left the Art Department with our own questions to ask: Would Ecotactical still be able to come to fruition? How would the context of the show develop during a pandemic? What would a virtual show look like for us? While the Art Department was grappling with these questions, both our staff and the artists were navigating the new reality in their personal lives. Artists’ access to their studios was altered, and some as parents now had the added responsibility of child care during work time. Those as professors at universities were adapting to online teaching. Some were forced to relocate, making site visits impossible. Meetings about the outdoor installations on our trails became difficult to plan.

With determination and perseverance from our staff and the artists, we were thrilled to finally present Ecotactical on September 21, almost six months after its originally scheduled debut. Armed with plenty of hand sanitizer and capacity guidelines we were able to open our gallery doors and celebrate our reopening in our first virtual reception. Having a way to safely reconnect after much time apart and to process the impact of the pandemic together provided a moment of needed healing. As we look towards Earth Day 2021, we embrace one of the lessons the pandemic has taught us: the importance of spending time together and the value of the natural world around us.

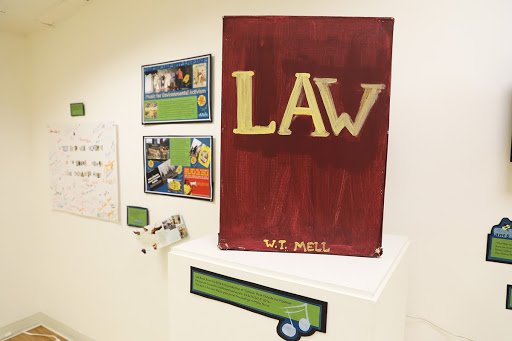

Installation view of Ecotactical by Liz Jelsomine

At this milestone in Earth Day’s legacy, what are your thoughts on engaging communities in Earth Day activism and in your artistic process specifically?

I am still struggling with how to make community activism tangible to kids, and how to have students see the results of their hard work. In the original version of our musical, the villains, “Businessman 1” and “Businessman 2,” come around and realize that green jobs are the way to go. But that ending never sat well with me. It felt too Pollyanna. So we rewrote the ending to reflect what actually happens in real life: The Businessmen decide that the oil refinery expansion project (which the child protagonists are fighting against throughout the play) is not right for them after all and they chalk it up to various other reasons, none of which is the kids’ activism: they wanted to spend more time with their families; they realized it was not financially viable at this time; etc. This is what children are up against in our world right now: the biggest culprits of environmental pollution will never admit when activism was successful. And it can be a slow process on top of that. I want to prepare young people for that, and also give them tools to fight back and ways to see what success looks like. The new song is called, ‘Totally Unrelated” and it hasn’t yet been recorded.

I had an Art History teacher in college who used to say, “All art is propaganda” and that always stuck with me. As a musician, an artist, and an art appreciator, I now see that anything you are planning to show in public becomes a statement. In my band, we are paying more attention to the messages in the songs we choose to play, because when you make art, a message will be conveyed whether you want that or not. So it’s important to think carefully about what you want that message to be. The same goes for teaching: whatever we decide to teach, we are making a statement about what we want future generations to know and how we want them to view the world. It is no small decision.

By Anya Rose (Ants on a Log), co-presented the installation Curious: Think Outside the Pipeline!, 2020

Family Concert with Ants on a Log at the Schuylkill Center (2020).

What is a new question about the environment that has arisen for you after making your artwork?

I’m watching and wondering, what will we do as individuals and communities, if our government won’t prioritize the Earth, and our systems are designed to fail our most vulnerable populations? I’ve been reading Emergent Strategy by adrienne maree brown. She continuously reminds us that the relational is the most important, and that nature already has the answers. If we as humans could only mimic what nature shows us, in its rhythms, cycles, and interdependence, we could start thriving. I am grateful for this kernel of hope right now.

By Anya Rose (Ants on a Log), co-presented the installation Curious: Think Outside the Pipeline!, 2020:

Installation view of Curious:Think Outside the Pipeline! in Ecotactical by Liz Jelsomine

As we were struck both personally and professionally with COVID-19 in the spring of 2020, the initial timeline of the exhibition Ecotactical: Earth Day at 50 had to change as well. How has the pandemic shifted your perspective on the environmental art world at large and your art practice specifically?

My project For The Future centers on community activism related to Earth Day throughout the history of the environmental movement. The content of the messages on the flags is meant to raise awareness of the activist actions of so many dedicated people: anonymous protesters at Earth Day and Climate marches, Greta Thunberg and the youth movement of Climate Strikers, Indigenous peoples defending some of the last remaining natural resources from extraction and pollution, and climate justice workers in urban environments fighting for the basic human right of healthy air, water and food access. The activism related to the environment is a crucial issue at the heart of our community’s health and prospects for the future.

The pandemic has crystalized my perspective on the environment. Rather than calling for attention at the periphery of social concern, environmental issues are now at the forefront. Looking at how our pandemic slowdown has allowed Earth to heal and how motivated the youth movement is on this issue, I am hopeful that the new administration sees how crucial listening to the science regarding climate change will be. Environmentally minded science fiction writers such as Octavia Butler and Margaret Atwood have envisioned what we are living through as a direct result of climate change. The key now is envisioning ways to live with mutual aid as a core value. Mutual aid between humans and between humans and the environment. I believe it will prove to be key to our survival.

By Julia Way Rix, presented the installation For The Future, 2020:

Installation view of For the Future on the Schuylkill Center’s trails by Liz Jelsomine