By Guest Contributor Angel R. Graham

I had the pleasure of speaking with LandLab artist Jake Beckman over the telephone recently. Jake explained that he is enjoying being a LandLab artist. His LandLab experience allows him to engage himself more with the outdoors, he says, conning him more deeply to the land.

Science and art are really similar in a lot of ways. You have to imagine the unknown.

J.B: I think the thread that ties most of them together is an interest in how things work. What are the processes that cause things to come into existence – things that we use, or part of our built environment, or things that we depend and rely on in society? A lot of [my art] looks at materials and industrial ingredients.

A.G: Who inspires you artistically?

J.B: That’s a tough question. I read a lot. I am really interested in a wide range of things, popular science to scientific journals to sociological studies…I like work that engages in kind of a dialogue that is accessible. [I like] public work that is playful but also has some sort of critical sense to it. I like work that reaches beyond art and engages with people.

A.G: How did you connect with LandLab?

Jake explained that he received a fellowship through the Center for Emerging and Visual Artists (CFEVA). Since they were aware of his science background, CFEVA let him know about the opportunity to work with LandLab.

J.B: I had been to the Center a couple of times before I ever even heard about LandLab. I just enjoyed the grounds. My wife and I had a garden plot [at the Center].

A.G: What does it mean to you to be a LandLab artist?

J.B: It’s wonderful to be outside, to be thinking about making work in an outdoor environment. You know, I’m really hoping to honor this kind of spirit of engagement with the outdoors that I think the Center is trying to foster by making art that feels like it’s part of that dialogue and part of a process. It is part of this ecosystem, bringing it to life in a different way. I think it’s really been a wonderful change of perspective for me in thinking about my work and I’m really grateful for that. When you make work that lives in this white box of a gallery, things sometimes feel a little claustrophobic. This has been a nice experience to help to balance that and be engaged a little bit more.

A.G: What inspired your LandLab piece?

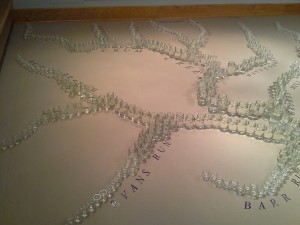

J.B: The whole overview of the project that I am working on and that I proposed is really based on my investigation into research about soil formation: the way that soils are so important for the ecology of any natural system. They are really unique in a lot of ways. They are not like normal ecosystems that we think of … because everything is happening at such a different scale and a different time period. So you think of geological processes. The project encompasses a lot of those ideas. Two or three pieces that I am thinking of installing over the course of the fall, the winter, and into next spring really look at soil formation through these lenses of time-periods, if you will. One of them is really going to look at the way stone dissolves over time and that is obviously going to be on a different time scale than the one I am making out of wood which will happen over the course of decades or less than that.

A.G: What is your definition of art? What is art to you?

J.B: In some way, it is sort of philosophy made material…and you know art is many things to many different people. What it means to me? [laughs] I don’t know; I think it’s play, it’s serious play. I think some of it is convention and some of it people understand when you call something art, you are giving them license to think beyond what is it, what does it do, how does it work. I think when you call something art, even though it is this nebulous term, it allows for some loosening of boundaries. …It’s kind of frustrating but also freeing, and really fun, how many different disciplines I can borrow from… and then incorporate into [my art].

A.G: What you want people to take away from your work?

J.B: I guess I’m interested in drawing connections between things that we don’t necessarily connect. In my life, I’m not really connected to the land in a way that I feel like I want to be. I live in a city, in a place that is humming with activity, but it is a lot of human activity and a lot of infrastructure and I feel somewhat disconnected [from the land]. I don’t know that my work actually reconnects people or anything like that but I am hoping at some one point it’ll get to that stage where it forms those connections for other people as well as me.

A.G: How does your artwork connect to science?

J.B: Not as much as I would like. I think that science is the process of asking questions, posing questions, and imagining ways to answer to them. It is dealing with … mystery or exploring unknowns. I think frequently my work strives to some small degree, to pose interesting questions and elicit that sense mystery and wonder that I think science has. But I don’t think I’ve gotten there [laughs]. But I think science and art are really similar in a lot of ways. You have to imagine the unknown. You have to be really creative and come up with possible ideas; in science you then go on and test and [in] art you go on and make.

About Angel R. Graham

About Angel R. Graham

Angel is currently a student at Mitchell College in New London, CT majoring in Environmental Studies with a minor in Communications. After completing her undergrad studies, she wants to continue on to grad school where she plans to complete a Master’s degree in Public Health. Angel hopes to become a public policy writer for the EPA or FDA.

I’m Leslie Birch, and I’m very curious about Philadelphia’s water. Last Thursday, I felt a bit nervous as I headed my car down the long driveway towards the Schuylkill Center. Having looked at records online for water quality in this watershed, I’ve seen mixed reports. We are located downstream from some heavy-duty coal and energy industries and also share our waters with many manufacturing industries. What hope can there be? Well, after meeting Sean Duffy, Director of Land and Facilities, I was assured there actually is a shining star – apparently the Center has some of the best water quality around because it is spring fed. Originally the land was made up of farms, and in those days you had to have a well to get your water, so this makes a lot of sense. Now, most people are connected to a community source of water through pipes, so the fact that the Center still has its original clean water source is good news.

I’m Leslie Birch, and I’m very curious about Philadelphia’s water. Last Thursday, I felt a bit nervous as I headed my car down the long driveway towards the Schuylkill Center. Having looked at records online for water quality in this watershed, I’ve seen mixed reports. We are located downstream from some heavy-duty coal and energy industries and also share our waters with many manufacturing industries. What hope can there be? Well, after meeting Sean Duffy, Director of Land and Facilities, I was assured there actually is a shining star – apparently the Center has some of the best water quality around because it is spring fed. Originally the land was made up of farms, and in those days you had to have a well to get your water, so this makes a lot of sense. Now, most people are connected to a community source of water through pipes, so the fact that the Center still has its original clean water source is good news.