By LandLab Resident Artist Leslie Birch

I’m Leslie Birch, and I’m very curious about Philadelphia’s water. Last Thursday, I felt a bit nervous as I headed my car down the long driveway towards the Schuylkill Center. Having looked at records online for water quality in this watershed, I’ve seen mixed reports. We are located downstream from some heavy-duty coal and energy industries and also share our waters with many manufacturing industries. What hope can there be? Well, after meeting Sean Duffy, Director of Land and Facilities, I was assured there actually is a shining star – apparently the Center has some of the best water quality around because it is spring fed. Originally the land was made up of farms, and in those days you had to have a well to get your water, so this makes a lot of sense. Now, most people are connected to a community source of water through pipes, so the fact that the Center still has its original clean water source is good news.

I’m Leslie Birch, and I’m very curious about Philadelphia’s water. Last Thursday, I felt a bit nervous as I headed my car down the long driveway towards the Schuylkill Center. Having looked at records online for water quality in this watershed, I’ve seen mixed reports. We are located downstream from some heavy-duty coal and energy industries and also share our waters with many manufacturing industries. What hope can there be? Well, after meeting Sean Duffy, Director of Land and Facilities, I was assured there actually is a shining star – apparently the Center has some of the best water quality around because it is spring fed. Originally the land was made up of farms, and in those days you had to have a well to get your water, so this makes a lot of sense. Now, most people are connected to a community source of water through pipes, so the fact that the Center still has its original clean water source is good news.

The tricky news is the issue of storm water runoff. Sean said that in the last six years, he’s never seen it so bad, and certainly this is a result of what’s going on with the climate. I don’t want to argue about what to call this global warming, but I do want to understand the resulting chaotic weather and natural disasters that are occurring. Storm water runoff is one of those disasters. I’m sure some of you have seen this damage first hand at the shore with hurricane Sandy or even here in Philadelphia with the recent flooding. This year I had a friend who was preparing to evacuate as her garage became flooded. Many people’s cars were considered “totaled” after this recent storm, along with furniture and sentimental items. I’ve also assisted in flood preparation and clean-up at the historic Canoe Club on the Schuylkill. I’ve seen first-hand the marks left by the water level on the first floor ceiling of the building, as well as the inches of thick silt left behind by the storm. I’ve even seen injured birds and a displaced baby heron desperately looking for its mother. Recently I was reminded that even people’s pets are later found as victims of these storms. So, this rushing water is something we need to face.

The tricky news is the issue of storm water runoff. Sean said that in the last six years, he’s never seen it so bad, and certainly this is a result of what’s going on with the climate. I don’t want to argue about what to call this global warming, but I do want to understand the resulting chaotic weather and natural disasters that are occurring. Storm water runoff is one of those disasters. I’m sure some of you have seen this damage first hand at the shore with hurricane Sandy or even here in Philadelphia with the recent flooding. This year I had a friend who was preparing to evacuate as her garage became flooded. Many people’s cars were considered “totaled” after this recent storm, along with furniture and sentimental items. I’ve also assisted in flood preparation and clean-up at the historic Canoe Club on the Schuylkill. I’ve seen first-hand the marks left by the water level on the first floor ceiling of the building, as well as the inches of thick silt left behind by the storm. I’ve even seen injured birds and a displaced baby heron desperately looking for its mother. Recently I was reminded that even people’s pets are later found as victims of these storms. So, this rushing water is something we need to face.

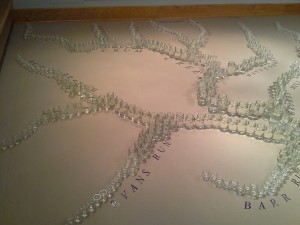

So, how does storm water run-off translate here at the Center? Sean was able to pinpoint the main areas of runoff on a map for me, and one of the major culprits is Port Royal Avenue. Often, roads have stormdrains that funnel rainwater away underground to be discharged into a larger waterbody during a storm – you’ve probably seen them around cities or even your neighborhood. But on Port Royal, there are no storm drains, and when it rains, the water still needs somewhere to go.

So, how does storm water run-off translate here at the Center? Sean was able to pinpoint the main areas of runoff on a map for me, and one of the major culprits is Port Royal Avenue. Often, roads have stormdrains that funnel rainwater away underground to be discharged into a larger waterbody during a storm – you’ve probably seen them around cities or even your neighborhood. But on Port Royal, there are no storm drains, and when it rains, the water still needs somewhere to go.

Instead, where Port Royal borders the Schuylkill Center property, there is a curb cut – the lower burm is removed to allow the water to leave the road surface. That moves the water straight off the road, leading it to travel above the ground’s surface down the hill towards Wind Dance Pond, causing erosion of the soils. You can see evidence of this in the picture. The pond soon overflows and causes water to divert towards the stream. Before you know it, you’ve got damage to the stream bed and possible trail damage and downed trees. This is cause for concern and really where my journey as an artist begins.

Instead, where Port Royal borders the Schuylkill Center property, there is a curb cut – the lower burm is removed to allow the water to leave the road surface. That moves the water straight off the road, leading it to travel above the ground’s surface down the hill towards Wind Dance Pond, causing erosion of the soils. You can see evidence of this in the picture. The pond soon overflows and causes water to divert towards the stream. Before you know it, you’ve got damage to the stream bed and possible trail damage and downed trees. This is cause for concern and really where my journey as an artist begins.

As a LandLab Resident, my goal was first to question the quality of the water, but that has now changed to question the movement of the water, specifically what happens before and after it enters Wind Dance Pond. Some things to consider may be the change in the height of water in the pond, the speed of the flow of water, and even the path the water takes as it exits the pond.

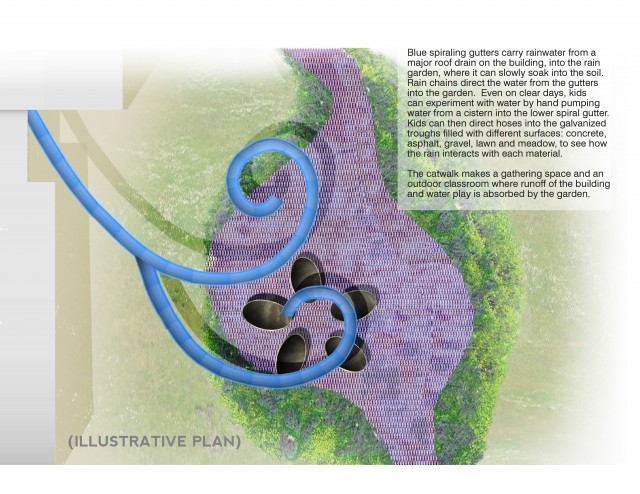

To gather information, I’ll need to do more scouts with Sean to see other forms of damage on the trails. I’ll also have to start researching equipment used to monitor these changes in water and figure out a way to keep it tethered under tough conditions. Finally, I’ll need to determine a way to make this information visual in a way people can understand, especially children.

So, what can I do about the trickle that I see leading to the pond, knowing it has the potential to become a torrent or flood with each major rainstorm? I’m not sure yet, but I know my answer will include community. Water is a powerful agent, and it will take more than one to tame it.

About the Author:

Leslie Birch is a tech artist with a love of Arduino microcontrollers. She lives near the Schuylkill River in the Art Museum area and loves birding. She also blogs at Geisha Teku. She can be found on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter.