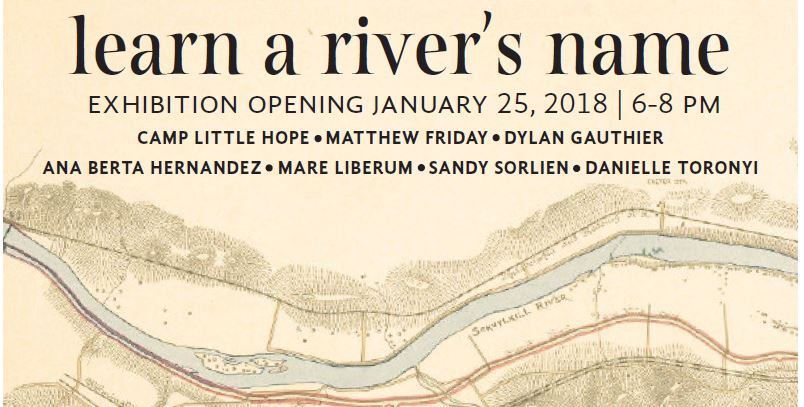

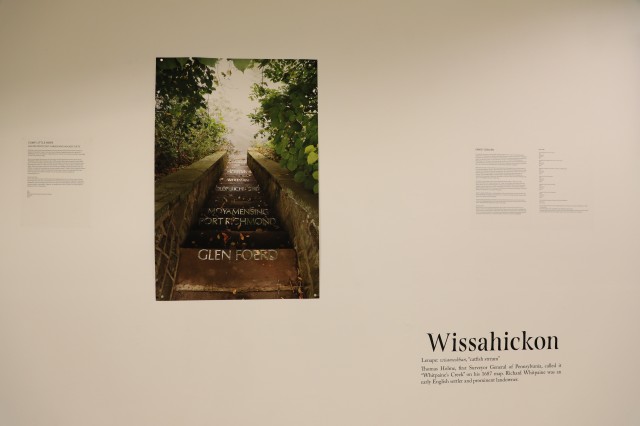

Learn a River’s Name

January 25 – April 21, 2018

Opening Reception January 25, 6-8pm

“Names are the way we humans build relationship, not only with each other but with the living world.” -Robin Wall Kimmerer

What’s in a name? It’s one of the first things we ask someone when we meet them, yet often quickly forgotten. It’s often something given to us by others, yet expected to serve as a distillation of our identity. Who gets to decide a name is often a question layered with power dynamics, whether it be a people, places, organisms, ecosystems.

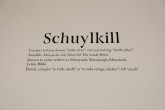

Yet, despite these complexities, in a 2017 New York Times op-ed, from which the title of this show is taken, Akiko Busch writes, “Giving something a name is the first step in taking care of it.” Thinking of bodies of water, a name is an opening, a prelude, a microcosm, a way to be known – a first step on the pathway to meaningful connections between people and nature. This exhibition was guided by this question: how can art help us to know a river’s name, to not only value it but know it, and therefore to seek to steward it? With a focus on water bodies in the Mid-Atlantic region, seven artists explored the rivers and streams that are neighbors to the Schuylkill Center — the Schuylkill, Delaware, Brandywine, and Hudson Rivers.

Learn a River’s Name consisted of artworks and art investigations that provided inroads to getting to know our rivers. It included projects that incorporated deep and focused engagement with a particular river, watershed, or stream. Featured alongside final products were relics from artistic processes by which an artist got to know a river in ways that might feel a lot like how we might get to know a person. Learn a River’s Name also included art works that revealed something unseen about a water body’s characteristics, its essential nature.

Wendell Berry wrote, “People exploit what they have merely concluded to be of value, but they defend what they love, and to defend what we love we need a particularizing language, for we love what we particularly know.” Learn a River’s Name was an invitation for us to better know a river near us, a call to action to know not just its name, but its features, its needs, and how we can be a good neighbor to it.

Gallery

Featured Artists:

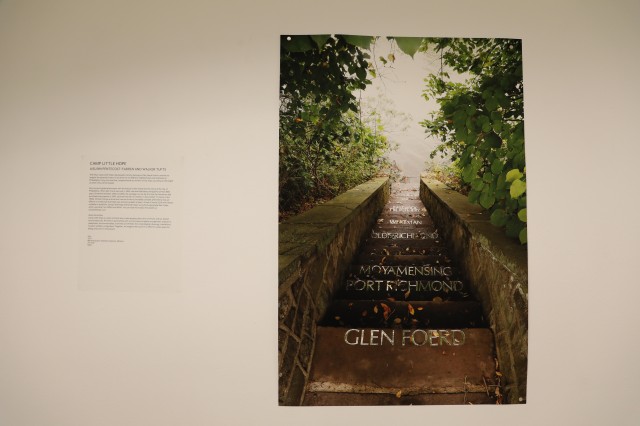

Camp Little Hope: Walker Tufts, Aislinn Pentecost-Farren

Camp Little Hope is a team of artists who create projects about the commons, and our shared natural resources. We work in partnership with communities and places as organizers, educators, researchers, environmentalists, archivists, and friends. We create objects, drawings, installations, museum exhibits, and gardens. Together, we imagine the future in an effort to create space for dialog and action in the present. Past commissions include Hidden City Philadelphia Festival, Arts Council of Wales, Elsewhere Museum, Western Carolina University, Glen Foerd on the Delaware, and Den Frie Center of Contemporary Art in Copenhagen, Denmark.

http://camplittlehope.com/#rise

Matthew Friday

Matthew Friday is an educator and transdisciplinary artist whose research focuses on the development of apparatuses and systems that examine and provoke new political ecologies. Working both collectively and individually, Matthew Friday’s projects have taken up issues of organized labor, community agriculture and watershed remediation. He is an active member of the ecosystem research and design collective SPURSE.

Matthew Friday studied at the Slade School or Art, the University of New Mexico and the Whitney Independent Study Program and has a MFA from Indiana State University. A committed educator, Friday has taught in a number of different institutions and settings including the State University of New York at Oswego, Empire College (NYC) and Ohio University and now serves as the graduate coordinator and associate professor of critical studies for the Art Department at the State University of New York at New Paltz. He has participated in presentations and studio critiques at Mildred’s Lane, the Art Institute of Chicago and Buffalo University and has published essays in October, the Journal of Modern Craft, the Journal Aesthetics and Protest and Art Journal.

About the work:

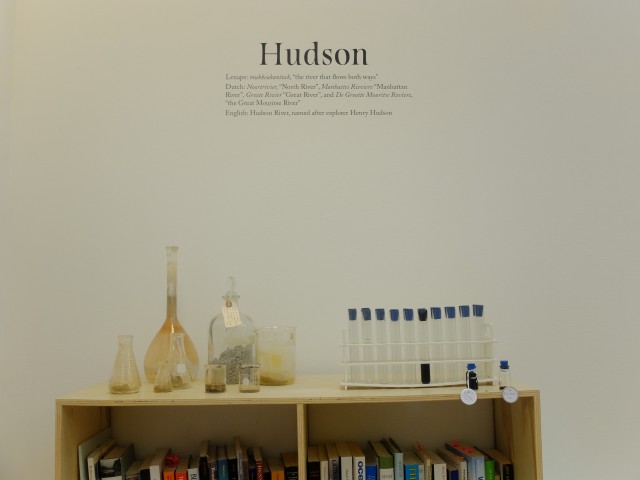

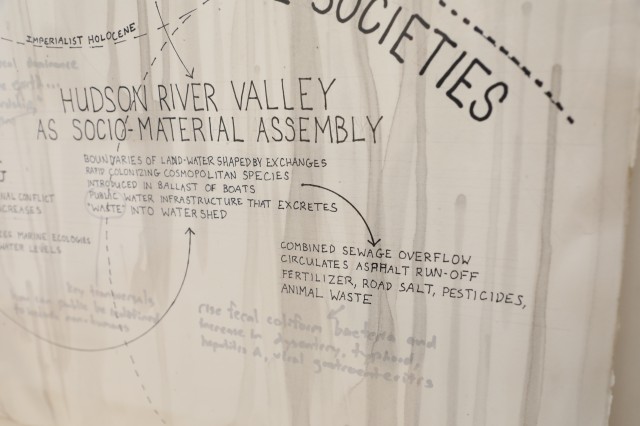

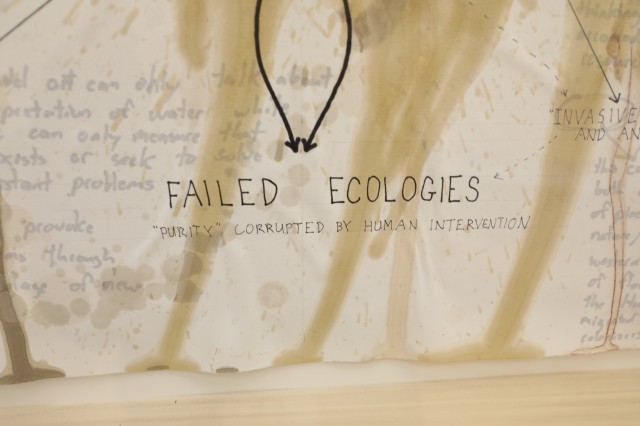

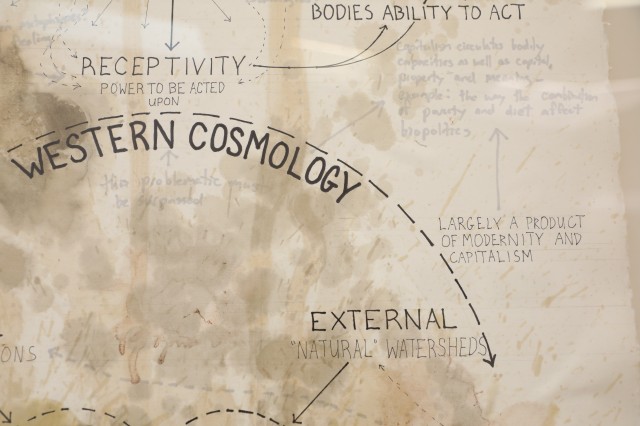

Facing the massive impact of global warming, deregulated power plants, crumbling infrastructure and toxic pollution there is a very real and pressing need to redefine our relations to our watersheds. The Hudson Valley of New York is home to a variety of environmental advocacy groups such as the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, Riverkeeper and the Department of Environmental Conservation. Working with these groups over the past several years, I’ve developed a series of public projects to cultivate environmental literacy and foster ecologically resilient systems. This installation includes a research platform that was used in support of these projects. Packed with a provisional library, water testing equipment and material samples, this platform packs into a mobile unit that has travelled the course of the Hudson River. Numerous tactile and interactive components encourage people to study and experiment with their own watersheds. The research from these collaborations inspired a series of diagrams that map out the connections, thresholds and histories of the Hudson River watershed.

There is something magical about diagrams; unlike images they don’t present an object but a set of relations. Speaking about maps and diagrams, the philosopher Gilles Deleuze made an interesting claim: they don’t simply represent things but rather iteratively build upon existing connections. This claim got me interested in thinking about how this process might be used in relation to ecological systems. A reconfiguration of the way we relate to our watersheds entails a radical rethinking of both our entangled ecological histories and the potentials for collaborating with these systems.

The materials used in these diagrams were produced directly from the Hudson River and they include everything from algae dyes to a pigment made from the waste coal taken from power plants. The larger painting, Pure Color of the Hudson (after Rodchenko), is a trace of the forces at work in the Hudson watershed. Made with the toxic polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) saturated river mud that General Electric dumped into the Hudson River, it is both a map and an index of the radical impact capitalism has had on the watershed.

Creating production methods for these materials requires understanding the implications these processes have on the watershed. In developing paints and papers from local sources, we become accountable to the plants and animals that are also dependent upon them; our health and their health become inexorably linked. For me, both ethics and aesthetics unfolds from this increased cycle of situated co-dependence.

https://www.wavehill.org/arts/artists/matthew-friday/

Installation:

Dylan Gauthier:

Dylan Gauthier is a Brooklyn-based artist who works through a research-based and collaborative practice centered on experiences of ecology, architecture, landscape, and social change. Gauthier is a founder of the boat-building and publishing collective Mare Liberum (www.thefreeseas.org) and of the Sunview Luncheonette (www.thesunview.org), a co-op for art, politics, and communalism in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. His individual and collective projects have been exhibited at the Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne (Paris), Parrish Art Museum, CCVA at Harvard University (Cambridge), the 2016 Biennial de Paris (Beirut), the Center for Architecture (New York), The International Studio and Curatorial Program (NY), EFA Project Space, and other venues in the US and abroad. His writings about art and public space have been published by Contemporary Art Stavanger, Parrish Art Museum, Urban Omnibus, Art in Odd Places, and Routledge/Public Art Dialogue, among others. In 2015 he was the NEA-supported Ecological Artist-in-Residence at the International Studio and Curatorial Program (ISCP); in 2016 he was a Socrates Sculpture Park Emerging Artist Fellow (NY), and this year he is the inaugural Artist-in-Residence at the Brandywine River Conservancy and Museum of Art, where his solo project highwatermarks is on view from October 2017 to January 2018. He co-curated (with Kendra Sullivan) the exhibition Resistance After Nature at Haverford College in spring of 2017. Gauthier received his MFA in Integrated Media Arts from Hunter College, CUNY (‘12), and teaches courses on emerging media and expanded cinema in the Department of Film and Media Studies at Hunter College, and ecological design in the School of Design Studies at Parsons/The New School.

About the work:

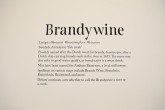

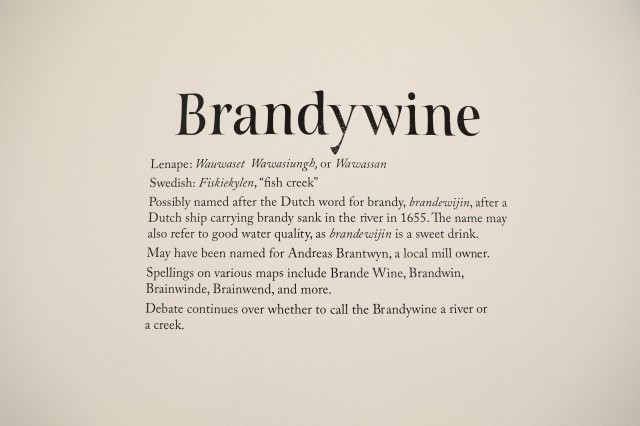

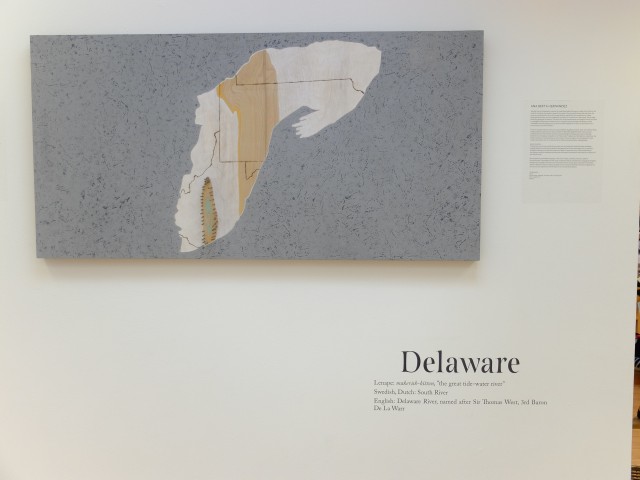

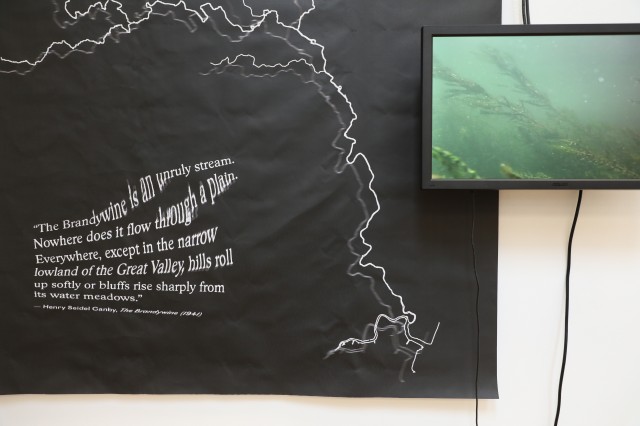

The work on display at the Schuylkill Center reflects a year-long residency I undertook with the

Brandywine River Museum of Art and Brandywine Conservancy in 2016/2017, focusing on the past, present, and future of the river. My work encountered the Brandywine River — sometimes called Brandywine Creek — as a deeply altered landscape, and aimed to inform a new public perception of the river and the communities who are connected by its run. The Brandywine River begins as flooded fields and small streams in the Honey Brook Township region, about an hour Northwest of Philadelphia. It builds into a stream and runs through former manufacturing towns like Coatesville and Downingtown, and Chateau country just north of the Delaware State Line, before entering Wilmington, joining up with the Christina River, and, finally emptying into the Delaware. Over its run, the river provides drinking water to half a million people, and serves as vital recreating and living space for diverse and varied human and nonhuman communities along the way. Over the past several hundred years, the River has been engineered and re-engineered to perform specific functions, from powering mills, to currently performing as part of a conservation “viewshed.” It is not just a river, nor is it just a line on a map. The work asks us to reflect on the uses (and misuses) of our common waterways, and to imbue a sense of complexity into our reading of the landscape that takes stock of a place’s natural and cultural history and the current issues that surround it.

http://www.brandywine.org/museum/exhibitions/dylan-gauthier-highwatermarks

Ana Berta Hernandez:

Ana Hernandez is a painter and sculptor currently living and working in New Orleans, Louisiana. She is a founding member of Level Artist Collective and a 2016 Joan Mitchell Foundation Artist-in-Residence recipient. Most notably, she has exhibited at The New Orleans Museum of Modern Art, Exhibit BE, Stella Jones Gallery, A Studio in the Woods, The Carroll Gallery at Tulane University, The Contemporary Art Center of New Orleans, The Ogden Museum of Southern Art and Tiger Strikes Asteroid Philadelphia.

About the work:

The Marcellus, 2017

Acrylic, charcoal, nails on wood panel

24” x 48” x 3”

Altering Internal Landscapes: In pursuit of unearthing bodies of Energy is a body of work that is the result of my research into areas of human rights abuses that stem from the practices and production of the oil and gas industry; specifically, their exploration of select geographical locations and the subsequent extraction of the resources “discovered” within these particular geological formations. This series is a visual representation of ecological trauma, it aims to highlight the dissection and destruction of a physical and psychological landscape, whose vulnerable and shifting body print can be traced and mapped by the scars of injury left on the environment and all who inhabit it.

Installation:

Mare Liberum:

Mare Liberum is a collective of visual artists, designers, and writers who formed around a shared engagement with New York’s waterways in 2007. As part of a mobile, interdisciplinary, and pedagogical practice, the collective has designed and built boats, published broadsides, essays, and books, invented water-related art and educational forums, and collaborated with diverse institutions in order to produce public talks, collaborative exhibitions, participatory works, and voyages. Mare Liberum has presented work at the Centre Pompidou – Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard University, the Parrish Art Museum, MASS MoCA, the Neuberger Museum, and EFA Project Space, among others. The collective is Jean Barberis, Dylan Gauthier, Ben Cohen, Stephan von Muehlen, Arthur Poisson, Sunita Prasad, and Kendra Sullivan.

ML’s work bridges dialogues in art, activism, and science, by remapping landscapes, reclaiming local ecologies, and observing and recording the overlaps of nature, industry, and the polis. The collective’s projects connect divergent constituencies with shared environmental concerns, create waterfront narratives ranging from the industrial to the personal, and catalyze the creation of engaged publics. Employing the methodologies of civic hacking, participation, open source, social sculpture, and temporary occupations, the collective extrapolates on Lefebvre’s or Harvey’s “right to the city” to include its neglected waterways.

Chloe Wang grew up alongside the Hudson River, and her aquatic engagements have ranged from oceanographic research to canoe voyaging to her current work in River Programs at Bartram’s Garden, which she is deeply immersed in learning about the Lower Schuylkill. Chloe recently graduated from Haverford College, where she studied chemistry and environmental studies and indulged whenever possible her love of visual and participatory art.

Sandy Sorlein

Sandy Sorlien is an environmental photographer and tour guide for the Fairmount Water Works, the education center for the Philadelphia Water Department. She has received three Fellowships in Photography from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, and taught photography at the University of the Arts for 12 years. Sandy was born and raised in the Schuylkill River Valley and lives in Roxborough near the Manayunk Canal. She fell in love with her native river while rowing on it out of Bachelor’s Barge Club on Boathouse Row. Sandy lectures throughout the watershed about her in-progress book project, Inland: Tracing the Schuylkill Canal from Coal Country to Philadelphia.

About the work:

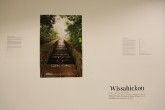

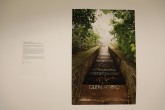

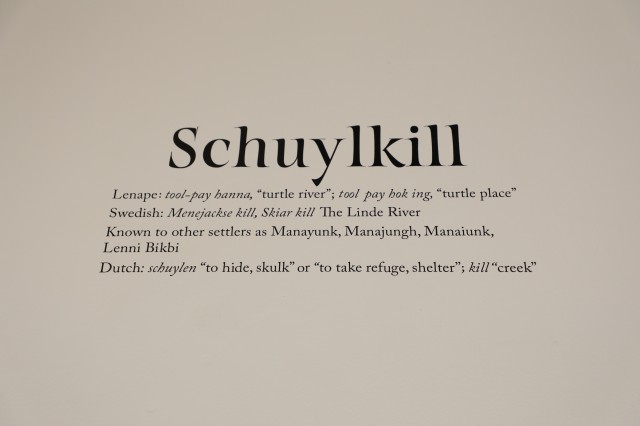

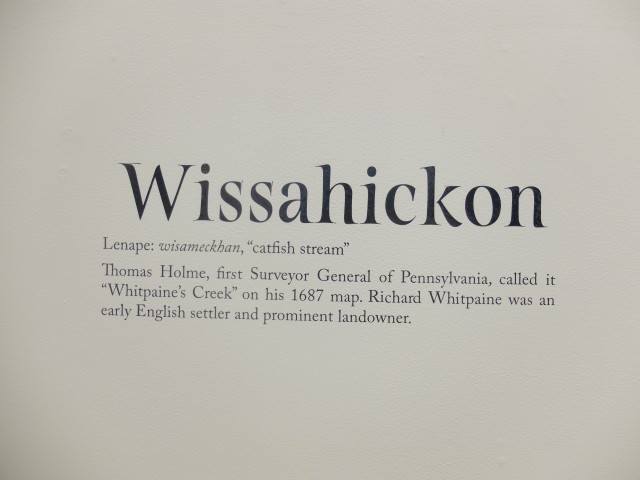

To know fully the name of the Schuylkill, meaning “hidden river” in Dutch, we should know its shadow river, the 200-year-old abandoned Schuylkill Navigation. Historians can understand this system as more than just canal sections, but Southeastern Pennsylvania’s canal communities have called it the Schuylkill Canal, or just “the canal.” My home Manayunk-Roxborough is one of those communities, but do we know we were once connected economically to Pottsville and Hamburg and Phoenixville, and to tidewater markets below the Fairmount Dam, by a 108-mile cleverly engineered, privately-owned slackwater navigation?

After years of research and bushwhacking, I have photographed most of what remains. There were once 32 dams, 46 miles of slackwater pools, 62 miles of canals, and 120 locks. By 1828, the Schuylkill River was tamed from Port Carbon to Fairmount. Barges brought anthracite down from the mountains; the canals provided water power to factories. The Schuylkill Navigation literally fueled the Industrial Revolution throughout our watershed. Unfortunately, it also led to the pollution of the river, then and now the drinking water source for Philadelphia and three other cities.

The river’s recovery began with the Schuylkill River Desilting Project of 1947-51, the first government cleanup of a major American river. Today, the river flows more freely and has fifty species of fish, but much of the Navigation infrastructure was dismantled or buried; there was no thought of historic preservation. Often, photography is the only way, and there are wonderful black-and-white records of the infrastructure and canal town life before the desilting, in books like Along the Schuylkill and The Schuylkill Navigation.

My purpose is different. As a photographer, I’ve always been attracted to places like these strange inland landscapes, with their layers of civilization and clues to other lifetimes. They aren’t lost to history; they are still here.

Thanks to the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection for the use of the Profile, to Keith Yahrling at the Philadelphia Photo Arts Center for printing expertise, and to Karen Young at the Fairmount Water Works / Philadelphia Water Department for support of this project.

Danielle Toronyi:

Danielle Toronyi is a landscape architect and artist whose work is focused on how we collectively experience, change, and learn from ecological and artificial systems. Through research-creation practices Toronyi engages in critical disruption at the edge of landscape architecture. She creates sonic, visual, and visceral methods for revealing the emergence of resilient or unstable systems through analyzing the living world and built environment. Her work comprises data-driven multimedia installation, body-focused performance, drawing, and community design.

Toronyi earned her BFA from The University of the Arts in 2006, and her Master of Landscape Architecture from NC State University’s College of Design in 2012.

Danielle Toronyi is the Research Development + Knowledge Manager at OLIN – a landscape architecture, urban design, and planning studio – and leads OLIN LABS, a newly emergent community of practice committed to elevating collaborative design research and innovation in landscape architecture.

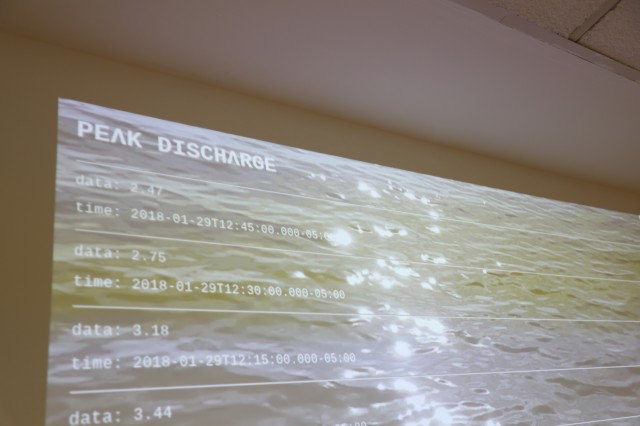

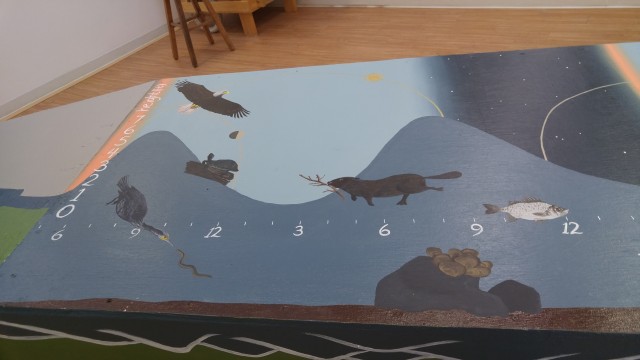

Peak Discharge is a revelatory bioacoustic soundscape – a sound and video piece that utilizes water pollution data to examine human impact on the land. The translation of data is an expression of visible and invisible forces acting upon the landscape. The underwater sounds of the Lower Schuylkill River are manipulated with recontextualized water quality data from the United States Geological Survey. Information representing individual ambient water quality markers is directly represented through a system of sound wave translations. The resulting sound piece confronts the listener with an audio illustration of the impact of human development on our natural systems.

https://www.danielletoronyi.com/peak-discharge/