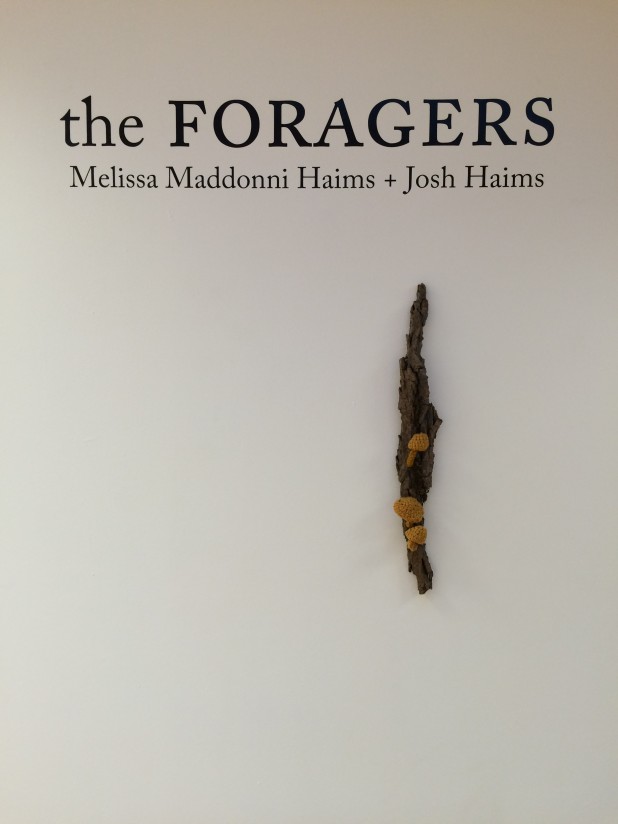

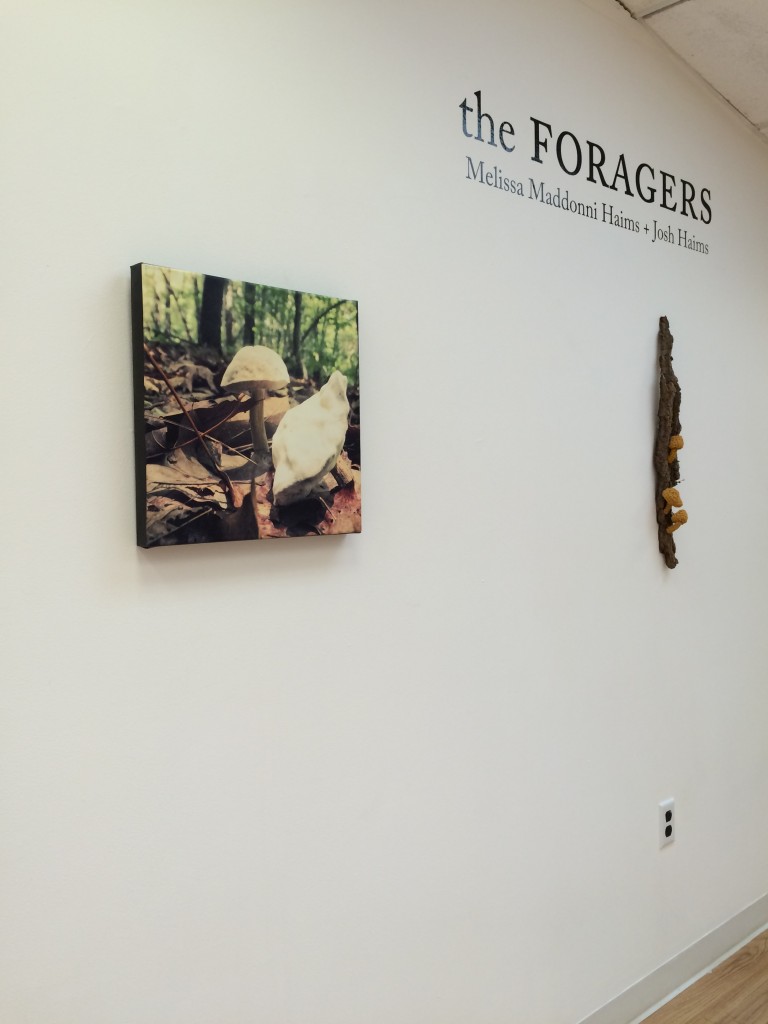

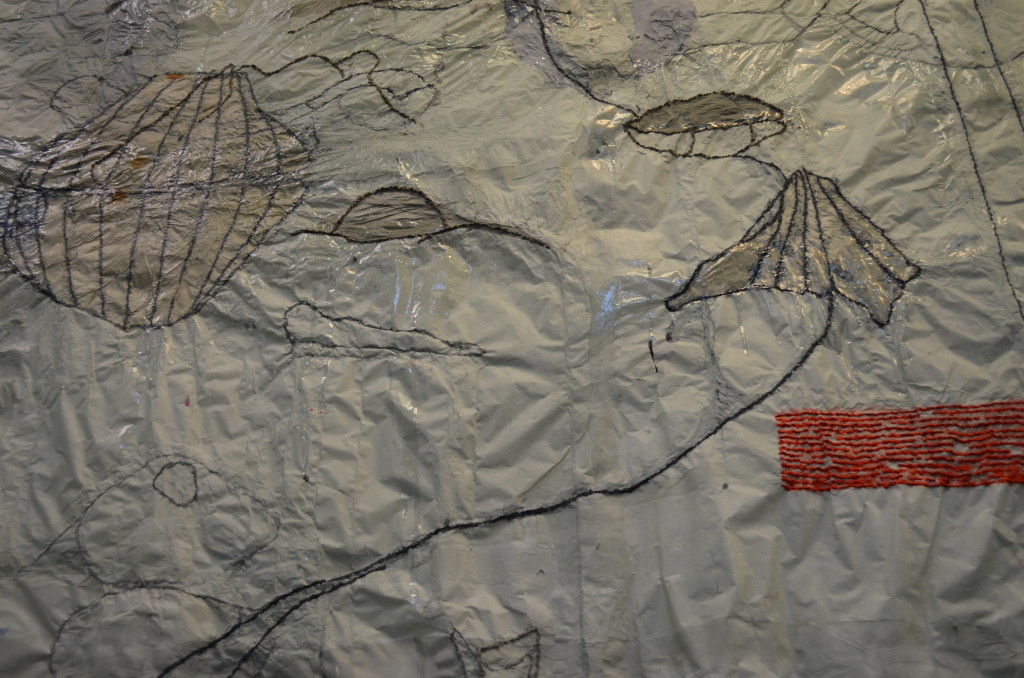

By Marguerita Hagan 2014 – 2015 LandLab Resident Artist, for the Native Pollinator Garden Residency with Maggie Mills and Ben Mills

Bee foraging Purple Hyssop: Native Pollinator Garden

“In the village, a sage should go about like a bee, which, not harming flower, color scent, flies off with the nectar.” – Anonymous, Dhammapada

Native Pollinator Garden: blue mistflower zinc etched plate by Maggie Mills, handcrafted chemical-free Douglas fir post by Ben Mills & pit fired ceramic bees by Marguerita Hagan & the community

One year has circled around completing our complex LandLab residency. We launched out of the gate enthusiastically to address Colony Collapse Disorder, the devastating loss of 1/3 of our honey bees with the Native Pollinator Garden. Our discoveries informed our process while simultaneously bringing to light simple truths, more questions, our collective opportunity, and the gravity of our choices.

Thank you to our guide, the Bee and to you for following our journey.

“We stand now where two roads diverge. But unlike the roads in Robert Frost’s familiar poem, they are not equally fair. The road we have long been traveling is deceptively easy, a smooth superhighway on which we progress with great speed, but at its end lies disaster. The other fork of the road — the one less traveled by — offers our last, our only chance to reach a destination that assures the preservation of the earth.” – Rachel Carson, Silent Spring

Maggie Mills & Ben Mills as we start the Native Pollinator Garden along the Widener Trail

What’s Essential?

Monoculture, tilling, GMOs/genetically modified organisms and chemical methods are standard conventional farming practices in the U.S. today and the belief is that chemicals are essential to growing food. The conventional systems often means that farmers need to buy and use only modified seeds, rather than saving seeds from their crops – in fact, farmers growing GMO seeds are legally prohibited from saving and planting any seeds from those plants. With the prevalence of GMO seeds, many wild plants are being pushed out of even the narrow margins alongside fields. Healthy forage is essential to bees, all pollinators, and to us.

Bee gathering pollen.

Finding Our Way Home

When bees and other pollinators come into contact with chemically treated flowering plants, their finely tuned nervous system and brain suffers dramatically. The chemicals destroy the bees’ GPS system, a lethal move for a bee who cannot survive outside the hive over 24 hours. This is just one piece of the complex issue.

Honeybees are something of an ambassador for other pollinators and their environment as they are the ones most intrinsically linked to humans through pollination of essential crops and wild plants. For the bees, their life mission is mutual benefit for the hive community.

This puts them in a powerful position to get our much-needed attention. And people are taking notice of the plight of the bees; and it’s about time since bees provide every 3rd bite we take. Farming that is dependent on honeybee pollination sees bees as a source of profit or loss, rather than a living part of the ecosystem. For example, almonds, California’s largest export are 100% pollinated by honeybees. Without bees to naturally pollinate crops to meet industry demands, a new tier of stress has been put into motion. To meet that demand, 90% of the bees in the U.S. are used as pollinating migrant workers, trucked from crop to crop around the country. Consider the fuel and costs required to keep this unhealthy cycle rolling.

Homesick

One of the first articles addressing the concern for our own health in regards to CCD: Our Bees, Ourselves- What Colony collapse says about chemicals and disease, New York Times, Tues, July 15, 2014, by Mark Winston.

Genetic seed modifying began in the U.S. in the early sixties, over 50 years ago. Since then it’s grown exponentially. Today, it is often considered one of the causes of Colony Collapse Disorder. Our tiny eco ambassadors seem to be the Ghost of Christmas Future shaking us to wake up. The resilient honeybee has thrived for over 40 million years, until now.

The widespread collapse presents a clear message. In the long run, how will it affect us? We have Rachel Carson to thank for her decades of perseverance in making DDT illegal. The insecticide sprayed openly from trucks through neighborhoods with children playing in the fumigated fog was originally developed for chemical warfare in WWII.

As Rachel Carson put it, “How could intelligent beings seek to control few unwanted species by a method that contaminated the entire environment and brought the threat of disease and death even to their own kind?”

Positive Shifts under our Feet

Native Pollinator Garden: Purple Hyssop zinc etched plates by Maggie Mills, hand crafted chemical-free Douglas fir post by Ben Mills, and Pit fired ceramic bees by Marguerita Hagan & the community

Good News!

We are in an Agrarian Renaissance and holistic practices are on the rise with no till, chemical-free, and organic farming. These principles are alive in our own practices. Innovative farmers have stepped off the chemical wagon of conventional practices to weather the transition and investment in sustainable farming. I’ve recently come across a few examples to share:

The Soil Will Save Us by Kristin Ohlsen is an exciting work sharing the journey of those listening and responding to our environment successfully. It is a thrilling return. Organic farmers working this way for decades are producing even during drought. Their reciprocal-minded process is enriching crops with carbon rich soil.

The Farm to Table concept is being delivered to more tables both at home and commercially. My LandLab teammates Ben and Maggie Mills have a year-round organic chemical-free garden- yes, even foraging in winter. As a master craftsman, one aspect of Ben Mills’ practice includes custom built chemical free raised beds.

Gotham Greens in Brooklyn is the world’s largest urban farm and expanding. Produce is harvested and served in restaurants within a few hours. Nell Thorn Restaurant in La Conner, WA has held the torch for years and is joined by sprouting conscious restauranteurs. The present Hand-Crafted Movement is in step with its Agrarian Partner utilizing a material from earth to fire to table: CLAY. It is my main means for sculpture and my line of Farm to Tableware. Chefs classically have sous chefs and now some have personal ceramicists creating works for their original cuisine.

Farm to Tableware by Margueritaworks with Harvest Scene Petroglyph (Canyonlands National Park) – planting & watering seeds

Forward Movement

Our immediate focus on the bees grew with the Native Pollinator Garden. The problem is complex but solutions are often simple and best ones start at home. The honeybee showed us it is not about the bees – it’s about the we. We are a part of the bee’s lives and they are a part of ours.

The mini messengers that brought us to this residency speak loud and clear: We are in this together.

Our Native Pollinator Garden provided forage and food for thought- starting with healthy seeds, native plants, and organic soil in chemical-free Douglas fir raised beds. As we wrap up our residency, we ceremoniously handed off the watering can to the Schuylkill Center. Like ongoing adventures, it’s a beginning. As the Native Pollinator Garden embarks on a new season, we leave you with an invitation to pollinate awareness.

Camper excavating an amazing pit fired ceramic bee from ashes the morning following the pit-camp fire.

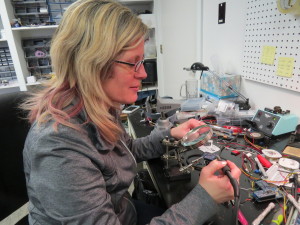

Marguerita Hagan laying ceramic bees made with the community in sawdust for Pit Fire at the 2014 Great American Backyard Campout.

Schuylkill Center campers gathering pollinator data during education event in the Native Pollinator Garden.

Maggie Mills leading Campers in Native Pollinator Garden: Learning and counting pollinators with Pollinator Data Sheets

Thank you!

Marguerita Hagan

For the Native Pollinator Garden:

Maggie Mills, Ben Mills, and Marguerita Hagan