By Eduardo Dueñas, Lead Environmental Educator | Para una versión en Español de este post, por favor ver aquí.

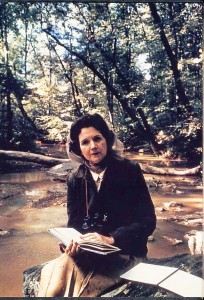

For as long as I can remember, I have always loved the scents, colors, and surprises of each day. I was a curious child who always liked to pick up rocks in the yard of my house to see what surprise awaited me underneath- a colorful beetle, a squirmy worm, or a family of ants. That same curiosity drove me to run outside everytime it rained to feel the rain and smell wet earth. I was the curious kid who would suck on blades of grass and throw stones into the river during a soccer game. From a young age, I was interested in plants and animals- passions which led me to explore many new places and meet incredible people working for positive change, ecological awareness, and conservation of our fragile planet.

After studying biology, I was left with no doubt that we must respect nature and carry nature within us.

It is critical for the wellbeing of everyone that children are able to grow up without physical or mental barriers removing them from nature. For some children and communities, it can be difficult to access natural areas or to find ways to connect with nature on a daily basis. When we help children to spend time in nature and understand the environment around them, they can become protectors and champions of our natural world.

In earning my master’s degree, I had the chance to study in depth the repercussions of human impact on nature – from unsustainable urban development to monoculture farming. It became clear to me that many modern lifestyles impact our own health and the health of the natural world around us. Because of this, I chose to focus my Master’s thesis on the need to readjust the way we learn about and perceive our surroundings- the natural world. I believe that education is our strongest hope to change the world and leave a positive legacy for future generations. As Baba Dioum said “”In the end, we will conserve only what we love, we will love only what we understand, and we will understand only what we are taught.”

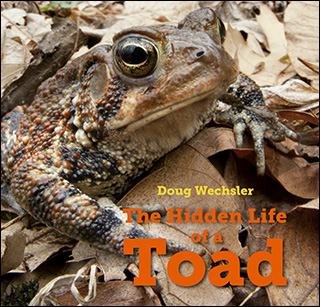

I feel lucky and inspired to work at a place like the Schuylkill Center, where every day we share and develop ideas about understanding and protecting our natural world. I love that our programs include children and adults of all ages, backgrounds, and ethnicities – like our after school programs with urban schools in Philadelphia, our outreach programs with Latino communities, and our family-friendly education and volunteer programs -like toad detour- for all ages.

Today, my office is the forest, where I work with children to guide them as they play and explore freely. During hikes, we draw, collect plants, seeds, or roots to make teas, sometimes we make art, or make notes about what we see in workbooks. It is fulfilling to me to be able to support a love of nature in my students, I see in them the curious kid I used to be.

Eduardo Duenas is an Environmental Educator at the Schuylkill Center. He first became involved with the Center as a volunteer before working full time with guided educational groups at the Schuylkill Center, after-school programs, and community outreach programs. He has a background in environmental studies, with a Master’s degree in Environmental Management and Sustainable Development. He also has experience as a classroom teacher and loves working with children of all ages.

Eduardo Duenas is an Environmental Educator at the Schuylkill Center. He first became involved with the Center as a volunteer before working full time with guided educational groups at the Schuylkill Center, after-school programs, and community outreach programs. He has a background in environmental studies, with a Master’s degree in Environmental Management and Sustainable Development. He also has experience as a classroom teacher and loves working with children of all ages.

We can address these problems by improving the soil and providing the roots of trees with a healthy environment to grow and develop. In our Fox Glen restoration site, as we planted new trees we covered the ground around them with wood chips to help the roots retain moisture. The wood chips will break down over time and add to the organic content of the soil.

We can address these problems by improving the soil and providing the roots of trees with a healthy environment to grow and develop. In our Fox Glen restoration site, as we planted new trees we covered the ground around them with wood chips to help the roots retain moisture. The wood chips will break down over time and add to the organic content of the soil.  Andrew has a master’s degree in landscape architecture and ecological restoration from Temple University. He hiked the Appalachian Trail from Georgia to Maine in 2005-2006.

Andrew has a master’s degree in landscape architecture and ecological restoration from Temple University. He hiked the Appalachian Trail from Georgia to Maine in 2005-2006.