By LandLab Resident Artist Leslie Birch

By LandLab Resident Artist Leslie Birch

For my LandLab residency, I’m working on the issue of storm water run-off here at the Center. Part of being a LandLab artist means working to re-mediate a problem using art, which is harder than just creating an installation that provides education. My hope is not only to have an artistic intervention, but also a scientific device to measure the amount of storm water run-off. In the past month, I’ve been in conversation with Sean Duffy, Director of Facilities, and Christina Catanese, Director of Environmental Art, about how the run-off from surrounding roads and neighborhoods impacts Wind Dance Pond, on the eastern side of the Center’s property. I’ve also been reading about the work of Stroud Water Research Center, because they’ve been constructing inexpensive water monitoring equipment that may be useful for my project. With art and science in mind, I came up with an idea – Storm Snakes.

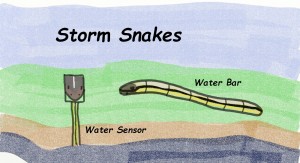

Storm Snakes is inspired by the sandbags often seen in flooding relief or construction sites. For the art intervention, burlap bags will be stitched together to create giant snakes that can be positioned in certain areas to divert water. The bags can be filled with natural materials like stones, wood chips, and cocoa matting. The exterior of the bags can be decorated to look like real snakes found in our region, through natural dye or cut out pieces of organic cotton. For the science part, a water monitoring device will be built and then mounted near the stream. It will use a sensor to detect changes in water depth and then relay the data back to a computer at the Center. This would help the Center learn more about how much runoff reaches their pond. The monitor can also be decorated to resemble a snake, so it is friendly looking and camouflaged with the environment.

Storm Snakes is inspired by the sandbags often seen in flooding relief or construction sites. For the art intervention, burlap bags will be stitched together to create giant snakes that can be positioned in certain areas to divert water. The bags can be filled with natural materials like stones, wood chips, and cocoa matting. The exterior of the bags can be decorated to look like real snakes found in our region, through natural dye or cut out pieces of organic cotton. For the science part, a water monitoring device will be built and then mounted near the stream. It will use a sensor to detect changes in water depth and then relay the data back to a computer at the Center. This would help the Center learn more about how much runoff reaches their pond. The monitor can also be decorated to resemble a snake, so it is friendly looking and camouflaged with the environment.

When I shared my idea with Sean and Christina, I wasn’t really sure what to expect. Their reactions were partly surprise, as the solution was more fun than traditional ones used in the field, but there was also excitement. Sean explained that Storm Snakes would actually improve the soil. Their wood chips will break down, increasing the fungal community – it’s what they feed on. I may not know much about soil chemistry, but this tidbit about fungus quickly made me a Storm Snake advocate! Plus, having data about storm water run-off could help the Center obtain funding for future remediation projects. It seemed like a win-win – Storm Snakes was official.

Recently I secured Stroud Water Research Center as a partner, which is awesome! They’re very interested in adding data about the Center’s stream to their database and in tackling another water monitoring set-up. In this case, I’m looking for the monitor to be as inexpensive as possible, while yielding science-worthy data. I hope to help Stroud by documenting my build of the water monitoring system—a tutorial will enable other citizen scientists around the world to create stream monitoring systems.

However, before I build anything, I first have to do more investigation of the storm water run-off. So, I went back to the Center this week for a hike with Sean and Christina. Although I already knew about one channel that had formed from the run-off on the hill, Sean took me to another area that showed an even larger channel. I’ve nick-named it the “Schuylkill Grand Canyon” as it was large enough to hold multiple people. Christina, who has a background in hydrology, was astounded by its size. Is the run-off still moving down this large channel? Is the smaller channel formed from this larger one? Where exactly is water entering from the road? These are the questions I have now, and my next step is to film a rain storm. So, stay tuned as my rain mystery continues.

However, before I build anything, I first have to do more investigation of the storm water run-off. So, I went back to the Center this week for a hike with Sean and Christina. Although I already knew about one channel that had formed from the run-off on the hill, Sean took me to another area that showed an even larger channel. I’ve nick-named it the “Schuylkill Grand Canyon” as it was large enough to hold multiple people. Christina, who has a background in hydrology, was astounded by its size. Is the run-off still moving down this large channel? Is the smaller channel formed from this larger one? Where exactly is water entering from the road? These are the questions I have now, and my next step is to film a rain storm. So, stay tuned as my rain mystery continues.

Until next time,

Leslie Birch

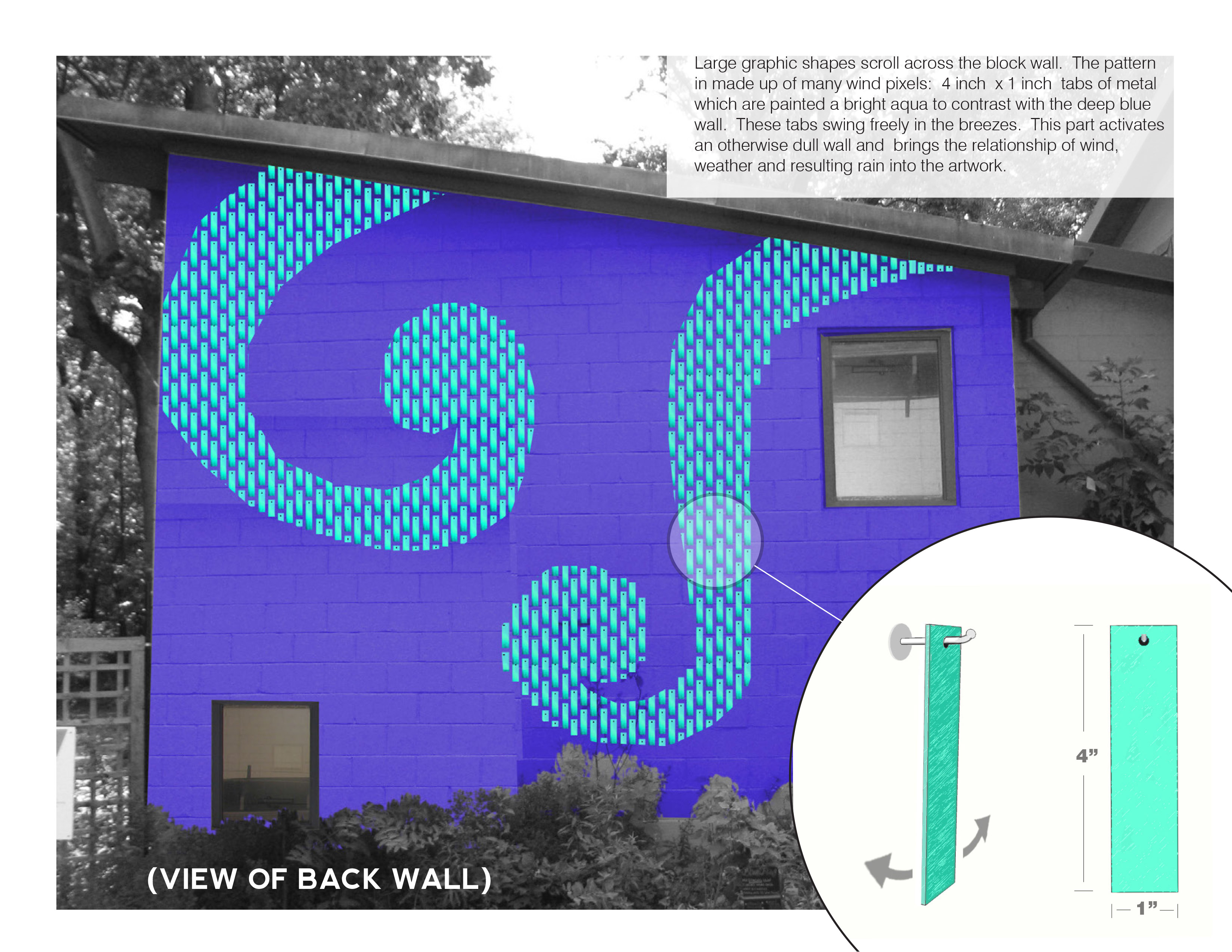

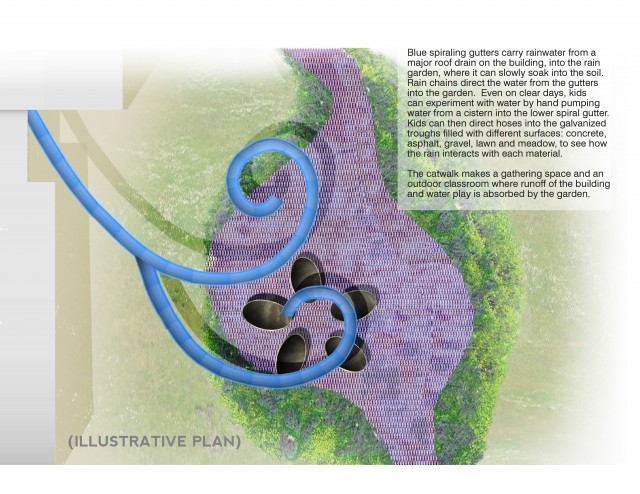

Rain is usually given a long narrow space to inhabit: gutters, downspouts, underground pipes. People can walk practically anywhere in a building and on the surrounding landscape. What if this paradigm got turned on its head? Give people a more narrow path of movement around a site while rain gets plenty of space to spread out and linger? How would our built environments change? And how would it change our relationship to rain?As an eco-artist, I want art to be an advocate of rain. Art is good at giving meaning to the leftover or abandoned aspects of the world—and rain is one of those abandoned elements. Though a

Rain is usually given a long narrow space to inhabit: gutters, downspouts, underground pipes. People can walk practically anywhere in a building and on the surrounding landscape. What if this paradigm got turned on its head? Give people a more narrow path of movement around a site while rain gets plenty of space to spread out and linger? How would our built environments change? And how would it change our relationship to rain?As an eco-artist, I want art to be an advocate of rain. Art is good at giving meaning to the leftover or abandoned aspects of the world—and rain is one of those abandoned elements. Though a

![virginia-bluebells-clifty-1-20091[1]](http://www.schuylkillcenter.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/virginia-bluebells-clifty-1-200911.jpg?w=200)

![bloodroot-4[1]](http://www.schuylkillcenter.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/bloodroot-412.jpg?w=300)