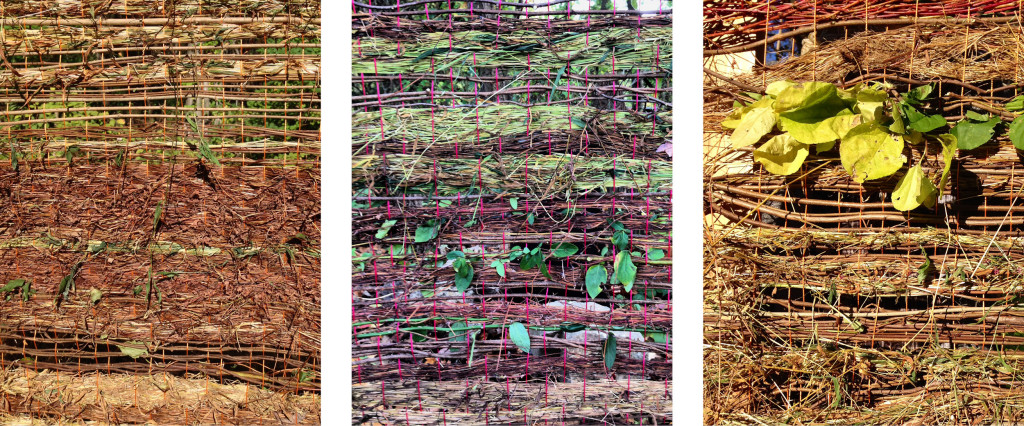

In my role as the Environmental Art Intern, I had the great opportunity to go through each and every one of the photos that were submitted to the amazing kaleidoscope of nature in the exhibition “Citizen’s Eye.” In the process of sorting through them, I had time to reflect on these snapshots, and on my own experiences in the outdoors throughout the pandemic. While there are many beautiful and eye-catching images, the ones that stood out to me most were those that documented time spent with other people. When I reflect on the time I spent outside over the last year, I am reminded of the close friends and family that I share these memories with. In a time of being hyper-aware of the spaces around us, nature provided a refuge and became the setting for all kinds of gathering. A place where we could still spend time with each other while also maintaining the distance we needed apart from each other to be safe and respectful.

What I see when I look through these images is a process of placemaking. Each photograph documents a way in which we are embedding emotional significance and new meaning into our natural environments. When we give these spaces new life, making them significant locations for living, gathering and communicating, we have transformed them into a place. While indoor spaces closed their doors to gathering, we turned to the outdoors to create new places to create memories. Celebration, exploration, connection, learning, mourning and many more rituals all took place in natural environments. Restaurants looked at parking lots and sidewalks and imagined new places for dining. This process was important in 2020. Natural placemaking reflected our needs to adjust to the circumstances, and it also reconnected us to a natural world that we are often at odds with. Whether or not you spent much time in the outdoors before the pandemic, your view of natural space definitely changed during the pandemic.

My hope is that post-pandemic, however that future looks, we will continue this process and continue to embed meaning into our natural spaces, whether it be the patch of grass on the sidewalk or the forest you went hiking through. Many were already doing this long before Covid-19 took ahold of our attention, but for others, time in quarantine allowed us to be more reflective and more presently focused on processes like this. We found a need to create new places, not by building or defining a space, but by being intentionally aware of what a space means to us and the memories that are connected to it.

I am glad to look through this collection of images and view the many ways in which we think about nature, both big and small, as important to our lives during a time of crisis and turmoil. As we imagine what futures await us, it is important to uphold these processes presently, and to imagine how natural space and its significance to us fits into these imagined futures.

—By CJ Walsh, Environmental Designer and former Art Intern at the Schuylkill Center.

Although this was not a heavy storm, at least I saw the puddling on Port Royal Ave., and I can imagine in a larger storm what the situation might be. In fact, seeing how difficult it is to actually record a storm makes the idea of a stream monitor even more valuable. So, I made a visit to

Although this was not a heavy storm, at least I saw the puddling on Port Royal Ave., and I can imagine in a larger storm what the situation might be. In fact, seeing how difficult it is to actually record a storm makes the idea of a stream monitor even more valuable. So, I made a visit to

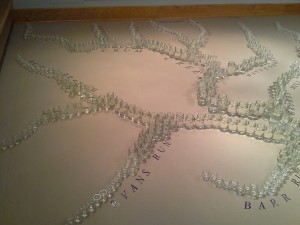

I’m Leslie Birch, and I’m very curious about Philadelphia’s water. Last Thursday, I felt a bit nervous as I headed my car down the long driveway towards the Schuylkill Center. Having looked at records online for water quality in this watershed, I’ve seen mixed reports. We are located downstream from some heavy-duty coal and energy industries and also share our waters with many manufacturing industries. What hope can there be? Well, after meeting Sean Duffy, Director of Land and Facilities, I was assured there actually is a shining star – apparently the Center has some of the best water quality around because it is spring fed. Originally the land was made up of farms, and in those days you had to have a well to get your water, so this makes a lot of sense. Now, most people are connected to a community source of water through pipes, so the fact that the Center still has its original clean water source is good news.

I’m Leslie Birch, and I’m very curious about Philadelphia’s water. Last Thursday, I felt a bit nervous as I headed my car down the long driveway towards the Schuylkill Center. Having looked at records online for water quality in this watershed, I’ve seen mixed reports. We are located downstream from some heavy-duty coal and energy industries and also share our waters with many manufacturing industries. What hope can there be? Well, after meeting Sean Duffy, Director of Land and Facilities, I was assured there actually is a shining star – apparently the Center has some of the best water quality around because it is spring fed. Originally the land was made up of farms, and in those days you had to have a well to get your water, so this makes a lot of sense. Now, most people are connected to a community source of water through pipes, so the fact that the Center still has its original clean water source is good news.