By LandLab Resident Artist Leslie Birch

Right now I’ve been experiencing some interesting emotional connection to my LandLab project. This may seem odd, as my project is probably the most tech oriented of the bunch! I can only describe it as this feeling of letting go of attached ideas and really just observing and listening, both to nature and the people that know it well. That is different for me, because most of the time my projects are conceived ahead of time so they can be “pitched” to the people that may green-light them. The process for LandLab is very different because the Schuylkill Center is trusting from past work that I have the ability to produce something interesting. They are looking for ideas, but they are not holding you to them. In fact if anything, they are excited by process and evolution, and the show in the gallery really speaks to that idea. The staff at the Center has been really great in encouraging my work, and allowing it to unfold. It is no different from allowing seasons to change, and I’m really experiencing that in my whole body. That’s it for the fuzzy stuff — let’s get back to the science!

Right now I’ve been experiencing some interesting emotional connection to my LandLab project. This may seem odd, as my project is probably the most tech oriented of the bunch! I can only describe it as this feeling of letting go of attached ideas and really just observing and listening, both to nature and the people that know it well. That is different for me, because most of the time my projects are conceived ahead of time so they can be “pitched” to the people that may green-light them. The process for LandLab is very different because the Schuylkill Center is trusting from past work that I have the ability to produce something interesting. They are looking for ideas, but they are not holding you to them. In fact if anything, they are excited by process and evolution, and the show in the gallery really speaks to that idea. The staff at the Center has been really great in encouraging my work, and allowing it to unfold. It is no different from allowing seasons to change, and I’m really experiencing that in my whole body. That’s it for the fuzzy stuff — let’s get back to the science!

You may remember that I wanted to get a glimpse of Port Royale Ave. and the Center’s property in the rain. It has been difficult to do this because this fall the rain storms have been coming at night, which would not be the best time for video. However, there was a morning when it was raining, and I rushed out of the house to record. Check out the video.

Although this was not a heavy storm, at least I saw the puddling on Port Royal Ave., and I can imagine in a larger storm what the situation might be. In fact, seeing how difficult it is to actually record a storm makes the idea of a stream monitor even more valuable. So, I made a visit to Stroud to check out their monitoring equipment, as well as Steve’s workspace. The property has nets for insects, buckets for leaves and other organic matter, and monitors for the stream — it’s a Disney World for scientists.

Although this was not a heavy storm, at least I saw the puddling on Port Royal Ave., and I can imagine in a larger storm what the situation might be. In fact, seeing how difficult it is to actually record a storm makes the idea of a stream monitor even more valuable. So, I made a visit to Stroud to check out their monitoring equipment, as well as Steve’s workspace. The property has nets for insects, buckets for leaves and other organic matter, and monitors for the stream — it’s a Disney World for scientists.

The tech space is full of controllers, sensors, cables, cases, batteries and canisters of water. It was encouraging that I was able to identify some of the parts in the bins, and Steve and I probably could have spent even more hours than we did just talking shop.

The tech space is full of controllers, sensors, cables, cases, batteries and canisters of water. It was encouraging that I was able to identify some of the parts in the bins, and Steve and I probably could have spent even more hours than we did just talking shop.

After seeing what was needed, Steve helped me to order some parts. So, now I have a datalogger and an ultrasonic rangefinder at my house. The datalogger is the main board in the circuit which will give instructions and allow for data to be collected. The ultrasonic sensor will measure the water depth throughout the day. So far this is a cost-effective set-up and there may be some room for another sensor. Right now I’m favoring conductivity, which looks at metals in the water. However, the sensor has to be able to withstand freezing temperatures, and Steve is currently testing a new one to see if it will be accurate. So, we will see which sensor wins. Steve has been testing equipment like this for years and is an expert on sensors and conditions.

One of the frustrating things about the field is that a good part may be discontinued, which leads to more testing of new products. Also, just because the paperwork says a part will operate in a certain way under certain conditions does not always mean this is true. So, the process is never-ending.

The next step in the process was to work on building a snake from burlap, and luckily I found someone interested in assisting me — Brenna Leary. Brenna recently graduated with a degree in environmental education and also has a love of plants. So, we’ve been having a lot of fun bouncing ideas back and forth. We spent an afternoon at the Center stuffing a casing of burlap with stones, wood chips, and coir. Then, we stitched the fabric shut and created the features of a tail, head and tongue with some tucks and scraps. It was a lot of fun and the resulting piece reminds me of the corn husk dolls I used to make as a child in Girl Scouts. They were featureless, but they had a beauty none-the-less, and so it is the same with the snake.

The next step in the process was to work on building a snake from burlap, and luckily I found someone interested in assisting me — Brenna Leary. Brenna recently graduated with a degree in environmental education and also has a love of plants. So, we’ve been having a lot of fun bouncing ideas back and forth. We spent an afternoon at the Center stuffing a casing of burlap with stones, wood chips, and coir. Then, we stitched the fabric shut and created the features of a tail, head and tongue with some tucks and scraps. It was a lot of fun and the resulting piece reminds me of the corn husk dolls I used to make as a child in Girl Scouts. They were featureless, but they had a beauty none-the-less, and so it is the same with the snake.

I started this post with this idea of change, and it may be apparent with electrical parts, but it is even more so with art. I first imagined my burlap StormSnakes to be painted with environmentally safe paint. However, someone reminded me that even natural things can react badly when put in touch with chemicals in stormwater run-off. So, you never know what kind of brew you are going to get running into the stream. I know there are all sorts of compromises we make daily, however, I didn’t want any risk in this, no matter how small. So, one day I was having lunch with another artist friend and we got into talking about the cool plant holders made of felt and other natural ways people deal with urban plantings. I suddenly remembered those crazy Chia Pets with the bad commercials. They were ceramic objects with a seed goop smeared onto them which would eventually sprout into odd topiaries. What an interesting idea to make snakes that had growing material on them. So, I talked to Melissa at the Center about the possibility of incorporating seeds or plugs onto my stuffed burlap snacks. She definitely had some recommendations and was excited since plants are her expertise. So, I hope to now perform a test in the greenhouse to see what emerges. Can I do stripes? Would I work with different plants and textures? I don’t know and I like that answer.

Although this was not a heavy storm, at least I saw the puddling on Port Royal Ave., and I can imagine in a larger storm what the situation might be. In fact, seeing how difficult it is to actually record a storm makes the idea of a stream monitor even more valuable. So, I made a visit to

Although this was not a heavy storm, at least I saw the puddling on Port Royal Ave., and I can imagine in a larger storm what the situation might be. In fact, seeing how difficult it is to actually record a storm makes the idea of a stream monitor even more valuable. So, I made a visit to

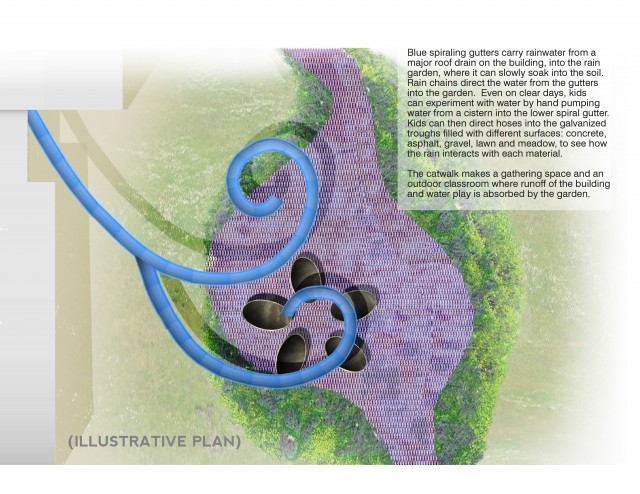

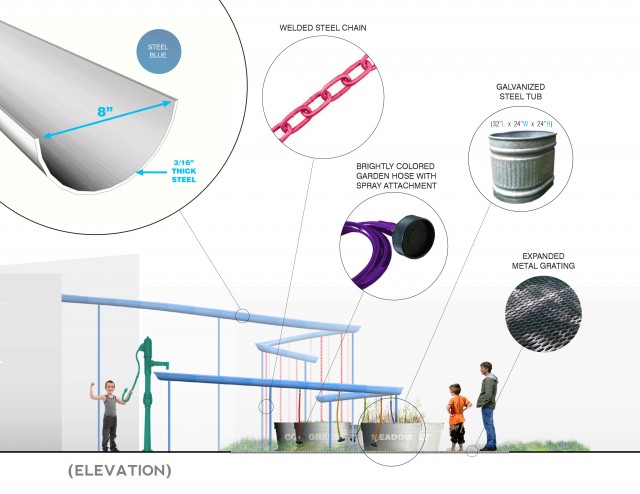

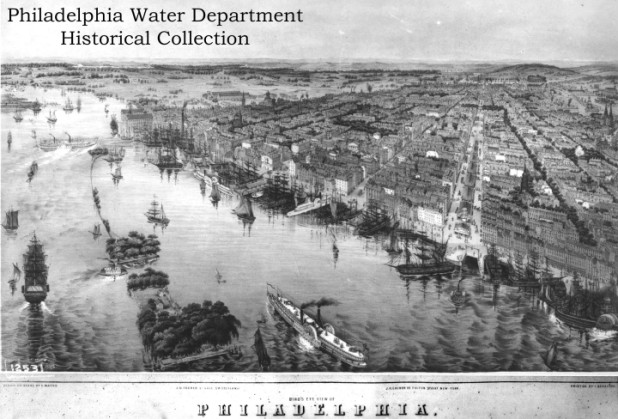

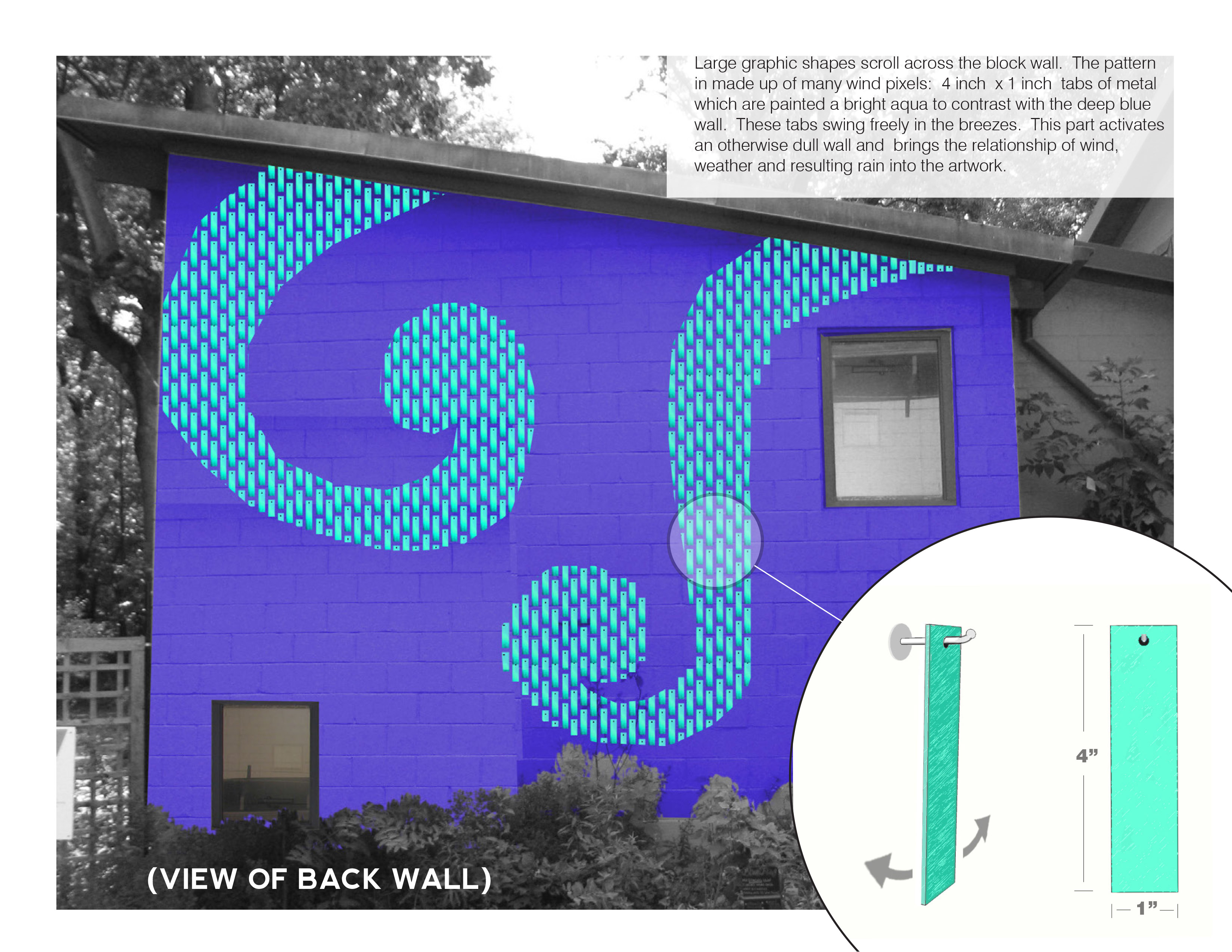

Rain is usually given a long narrow space to inhabit: gutters, downspouts, underground pipes. People can walk practically anywhere in a building and on the surrounding landscape. What if this paradigm got turned on its head? Give people a more narrow path of movement around a site while rain gets plenty of space to spread out and linger? How would our built environments change? And how would it change our relationship to rain?As an eco-artist, I want art to be an advocate of rain. Art is good at giving meaning to the leftover or abandoned aspects of the world—and rain is one of those abandoned elements. Though a

Rain is usually given a long narrow space to inhabit: gutters, downspouts, underground pipes. People can walk practically anywhere in a building and on the surrounding landscape. What if this paradigm got turned on its head? Give people a more narrow path of movement around a site while rain gets plenty of space to spread out and linger? How would our built environments change? And how would it change our relationship to rain?As an eco-artist, I want art to be an advocate of rain. Art is good at giving meaning to the leftover or abandoned aspects of the world—and rain is one of those abandoned elements. Though a