By Leslie Birch, 2014-2015 LandLab Resident Artist

My LandLab project started with the idea of examining water quality and morphed into understanding and mitigating stormwater run-off, the primary water quality concern facing the Schuylkill Center’s streams. It’s been interesting to see the changes along the way, much like a meandering stream. There’s been discovery in understanding how storms are affecting the land at the Center, brainstorming around ideas to deter the run-off, and definitely a period of inventing. Last we left off, I had been in discussion with Steve at Stroud Water Research Center about the sensors for my stream monitor. I learned that Steve was going to pay a visit to a canal community in Delaware for a monitor installation, and knowing it would involve boats, I was all in!

This community was going to experiment with oyster colonies to reduce the amount of algae in the water. As you can imagine, algae can build up and make it difficult for boats, so they were looking for a solution. They would need to test the water before and during the experiment in order to see if the oysters were successful. So, monitoring devices that could detect oxygen levels would be just the thing. Of course, the monitors would have to be installed in canals which were filled with saltwater–unlike the freshwater at our Center. It was interesting to see how the monitors were placed using a pole driver, which caused a bit of clanging. One family was particularly curious about the project, so I actually went ashore to explain it to them. They were so amazed and happy to hear about this possible sustainable solution for their community. All was going well with the monitors until we started testing. We got a negative read on conductivity–what??. Apparently the briny water caused a different affect on the sensor and had to be accounted for in the programming. It was a great lesson in coding, and Steve was able to tweak it to get the correct reading.

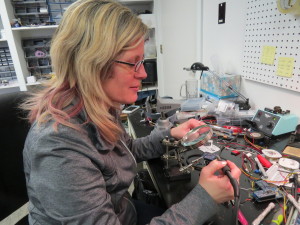

Back home, it was time to make some decisions on parts for my monitor. Steve knew I needed a water depth sensor to measure the amount of stormwater coming in, as well as something to do temperature and conductivity. For water depth, a specific ultrasonic sensor did well upon testing at Stroud, so Steve was excited about using it. Also, a new combination sensor for temperature and conductivity had come to market, and based on past sensors from the company, there was a sense that it would work well for my application. So, surrounded by some fun parts, I got started soldering.

I started with the main boards that would be used for the monitoring device. Since one little mistake in solder can cause a short circuit, I had Steve inspect each connection. Two opinions are better than one–especially late at night! Later I worked on soldering the parts for the XBee communication, which would allow the monitor to talk to another unit which would transmit the data to the internet. Besides soldering, there were also the project boxes that needed holes to be drilled. The drill will always be my favorite tool on the workbench :). It was a happy moment to be finished the assembly, but it was short lived when I moved onto testing. The ultrasonic sensor was definitely getting a reading, but the information was not transmitting properly. The data is supposed to get stored on an SD card on the unit and also transmitted to a website where it is formatted into a table. After double checking the hardware, Steve figured out that there was an issue with the Arduino code that had been uploaded. So, by tweaking one line, it was quickly repaired and we were back to testing. It’s so darn exciting when things work!

Video: https://youtu.be/1lkr7QeqoEU

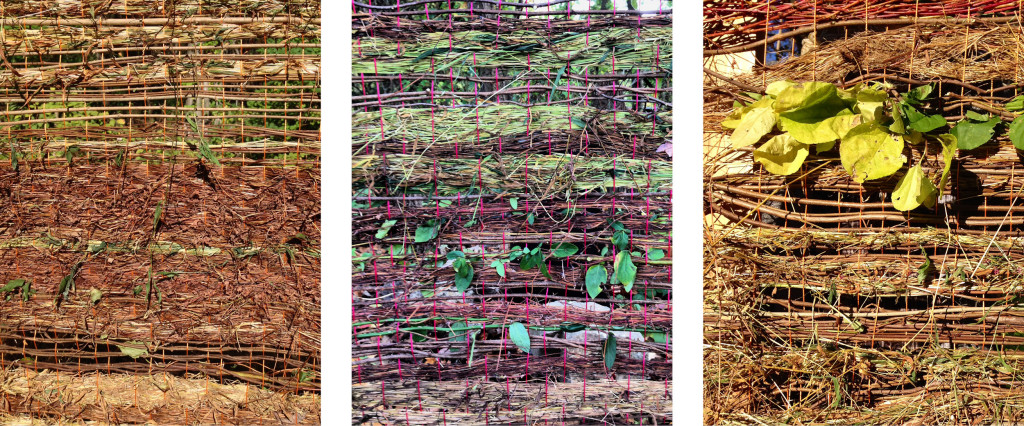

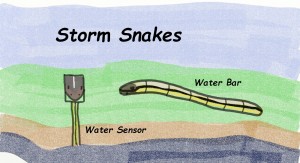

While Steve and I awaited a good-weather installation date for the monitor, I got together with Brenna to continue work on the larger Storm Snakes made of burlap. I remembered that the proportions had looked off on our small version, so I googled the dimensions of one of the largest snakes in the world for the new version. It seemed like each snake worked well with five coffee bean bags for length. Then, it was just a matter of trimming off the sides to create a skinnier snake. After I was finished stitching, I worked on stuffing the long casings of burlap with the mixture of coir, wood chips and stones. It took so long to shovel the materials into those casings, so my husband helped design a funnel out of a plastic plant pot to make the job easier. I successfully filled three large snakes, and they were looking quite plump. For decoration, you may recall I was interested in having plant material growing on the outside of the snakes. Well, I learned about moss graffiti and talked to a moss supplier in the Poconos, Moss Acres, to be sure this would be viable. A few days later I received a box of moss and after getting some large containers of yogurt, I was ready to roll.

On the day of installation, it took a team of us on a utility vehicle to place each of the three snakes–they were heavy! Christina Catanese (the Schuylkill Center’s Director of Environmental Art) had surveyed the team at the Center to determine the areas of the path that were most in need of stormwater protection. One ended up in the meadow to deal with parking lot run-off, another was located on a steep curve of a popular path where water often gathered and the final was placed on a path near Wind Dance Pond to slow down the water coming off Port Royal Ave– the inspiration point for the entire project. The next step was decorating the snakes. I mixed a moss yogurt slurry and attempted to paint it. It was tricky to apply, and in the end, I gave up on a brush and just used my bare fingers. It was fun creating the patterns, and I found that simple shapes worked best, as the mixture would easily crumble with intricate lines. The families passing by on the trail found them quite interesting.

As for the monitor installation, Steve and I finally found a good day to get it situated. I helped to hold parts as Steve hammered a mounting pole in the stream bottom. Now that things are in place, it is time for my favorite part–gathering data. So far the stream monitor seems to be collecting data fine. In its first week or so, it transmitted to the spreadsheet sporadically. This was due to the fact that the receiving station is set up in a metal building, and having problems getting a signal. Steve is currently testing different antennas that might be more suitable for this location. For now, we fetch the SD card and periodically upload, so there is some historical data currently on Stroud’s site to view, if you click on the table. Right now it is not transmitting at all, so Steve is also checking the code as it might have something to do with the way the system resets. No matter what, the data is still going to the SD card, so we will definitely have it.

One of the interesting things I’ve already learned from the data is that the conductivity is almost identical to a stream behind Stroud. I would have thought that our stream would have been more polluted as it stands near the bottom of the chain of watersheds leading to the Delaware River. Also, I thought that when a storm would come that there would be a big change in depth for quite a while, but apparently with urban streams, storm water comes in rapidly, but also dissipates quickly. So, you really have to look at each day’s numbers in order to view a difference. My hope is that these figures will be used as evidence of stormwater run-off so that future funding can be obtained to really mitigate the water coming off Port Royal Ave.

It has certainly b een an interesting adventure and I’ve learned so much about stormwater run-off. I’ve also had an opportunity to get more involved with science, and use my electronic skills for sustainability. I don’t think I could have found a better match for my interests, and I’m so thankful that our Center makes environmental art a priority. Getting to meet other like-minded artists has also given me hope that there is still the possibility of change in this world. It’s not going to be from corporations or governments, it’s going to have to come from people like you and me. My next step will be to create a tutorial that will be posted on Stroud’s website for creating the storm monitor. Thanks to open source solutions and the web, we can all share information and build our own solutions for environmental problems. This all ties into the idea of being a citizen scientist, which organizations like Public Lab and NASA are embracing. So, don’t be scared to be the scientist or the innovator. At the end of the day it isn’t necessarily who has the degree, it’s who is doing the work. There’s a place for all of us here on this planet, so be bold.

een an interesting adventure and I’ve learned so much about stormwater run-off. I’ve also had an opportunity to get more involved with science, and use my electronic skills for sustainability. I don’t think I could have found a better match for my interests, and I’m so thankful that our Center makes environmental art a priority. Getting to meet other like-minded artists has also given me hope that there is still the possibility of change in this world. It’s not going to be from corporations or governments, it’s going to have to come from people like you and me. My next step will be to create a tutorial that will be posted on Stroud’s website for creating the storm monitor. Thanks to open source solutions and the web, we can all share information and build our own solutions for environmental problems. This all ties into the idea of being a citizen scientist, which organizations like Public Lab and NASA are embracing. So, don’t be scared to be the scientist or the innovator. At the end of the day it isn’t necessarily who has the degree, it’s who is doing the work. There’s a place for all of us here on this planet, so be bold.

Although this was not a heavy storm, at least I saw the puddling on Port Royal Ave., and I can imagine in a larger storm what the situation might be. In fact, seeing how difficult it is to actually record a storm makes the idea of a stream monitor even more valuable. So, I made a visit to

Although this was not a heavy storm, at least I saw the puddling on Port Royal Ave., and I can imagine in a larger storm what the situation might be. In fact, seeing how difficult it is to actually record a storm makes the idea of a stream monitor even more valuable. So, I made a visit to

By LandLab Resident Artist Leslie Birch

By LandLab Resident Artist Leslie Birch

I’m Leslie Birch, and I’m very curious about Philadelphia’s water. Last Thursday, I felt a bit nervous as I headed my car down the long driveway towards the Schuylkill Center. Having looked at records online for water quality in this watershed, I’ve seen mixed reports. We are located downstream from some heavy-duty coal and energy industries and also share our waters with many manufacturing industries. What hope can there be? Well, after meeting Sean Duffy, Director of Land and Facilities, I was assured there actually is a shining star – apparently the Center has some of the best water quality around because it is spring fed. Originally the land was made up of farms, and in those days you had to have a well to get your water, so this makes a lot of sense. Now, most people are connected to a community source of water through pipes, so the fact that the Center still has its original clean water source is good news.

I’m Leslie Birch, and I’m very curious about Philadelphia’s water. Last Thursday, I felt a bit nervous as I headed my car down the long driveway towards the Schuylkill Center. Having looked at records online for water quality in this watershed, I’ve seen mixed reports. We are located downstream from some heavy-duty coal and energy industries and also share our waters with many manufacturing industries. What hope can there be? Well, after meeting Sean Duffy, Director of Land and Facilities, I was assured there actually is a shining star – apparently the Center has some of the best water quality around because it is spring fed. Originally the land was made up of farms, and in those days you had to have a well to get your water, so this makes a lot of sense. Now, most people are connected to a community source of water through pipes, so the fact that the Center still has its original clean water source is good news.