by Jenny Sabin

Figure 1 – Sabin’s myThread Pavilion for NYC Nike FlyKnit Collective; featuring a responsive Whole Garment knitted structure; image courtesy of Nike Inc.

Sustainable building practices should not simply be technical endeavors. They should include the transformation of existing built fabric into sustainable models that inspire both positive socio-cultural change and innovation in design, science, art and technology. Professor and architect, Michael Hensel at a recent symposium hosted by the Department of Architecture at Cornell University titled Sustaining Sustainability, underscored this notion (see full review by Sabin in The Architectural Review Issue #1381, March 2012). The symposium featured lectures by a diverse group of researchers and practitioners spanning multiple disciplines from biology to architecture who share a common concern for what Hensel has labeled ‘sustainability fatigue’. This symposium was not centered upon exhausted issues including energy, optimization and performance, which tend to dominate most conferences on sustainability in architecture today, but was instead focused on re-thinking the entire conceptual foundation for the project, one which fundamentally examines our relationship with nature and nature’s relationship with humans. Important to this shift, is a move away from purely technical solutions to environmental sustainability and a move towards an understanding that our built and natural environments are equally becoming the contexts for thriving hybrid ecosystems. How might architecture and art respond to issues of ecology whereby buildings and environmental interventions behave more like organisms in their built environments? And further, what role do humans play in response to changing conditions within the built environment using minimal energy consumption?

My work investigates the intersections of architecture and science, and applies insights and theories from biology and mathematics to the design of material structures. I am Assistant Professor in the area of Design and Emerging Technologies at Cornell University in the Department of Architecture, co-founder of LabStudio and principal of Jenny Sabin Studio, an experimental architectural design studio based in Philadelphia. I am interested in looking to nature for design models that give rise to new ways of thinking about issues of adaptation, change and performance in architecture.

Intersections between architecture, environmental art, materials science and biology offer fruitful models for ecological design thinking where collaborative pursuits offer new approaches to how we interact with nature in the built environment and to long term sustainable solutions in each of our individual fields.

Buildings in the U.S. alone account for nearly 40% of the total national energy consumption. Therefore, the design and production of new energy efficient technologies is crucial to successfully meet goals such as the Net-Zero Energy Commercial Building Initiative (CBI) put forward by the U.S. DOE, which aims to achieve zero-energy commercial buildings by 2025. LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) is a rating system launched by the U.S. Green Building Council for new construction and existing building renovations. The LEED green building certification program is the industry standard for accelerating global adoption of sustainable green building and development practices. While this certification program serves as a positive and productive report card for assessing a building’s impact upon its environment, it ultimately enforces a short-term ‘check box’ mentality over long term and systemic ecological design thinking. Ecological design thinking requires a radical departure from traditional research and design models in architecture, art and science with a move towards hybrid, trans-disciplinary concepts and models for collaborating. Although there have been tremendous innovations in design, material sciences, bio- and information technologies, direct interactions and collaborations between scientists, architects and artists are rare. All of this is regardless of the fact that science, engineering, art and architecture all share the need to comprehend key social, environmental and technological issues. One approach is to couple architectural designers with engineers and biologists within a research-based laboratory-studio in order to develop new ways of thinking, seeing and doing in each of our fields.

Since the official public launch in the fall of 2010 of our National Science Foundation (NSF) Emerging Frontiers in Research and Innovation (EFRI) Science in Energy and Environmental Design (SEED) project titled, Energy Minimization via Multi-Scalar Architectures: From Cell Contractility to Sensing Materials to Adaptive Building Skins, I (Co-PI) along with Andrew Lucia (Senior Personnel) have led a team of architects, graduate architecture students and researchers in the investigation of biologically-informed design through the visualization of complex data sets, digital fabrication and the production of experimental material systems for prototype speculations of adaptive building skins, designated eSkin, at the macro-building scale. The full team, led by Dr. Shu Yang (PI), is actively engaged in rigorous scientific research at the core of ecological building materials and design. Our project contributes to an area within architecture called responsive architecture while also presenting a unique avant-garde model for sustainable design via the fusion of the architectural design studio with laboratory-based scientific research.

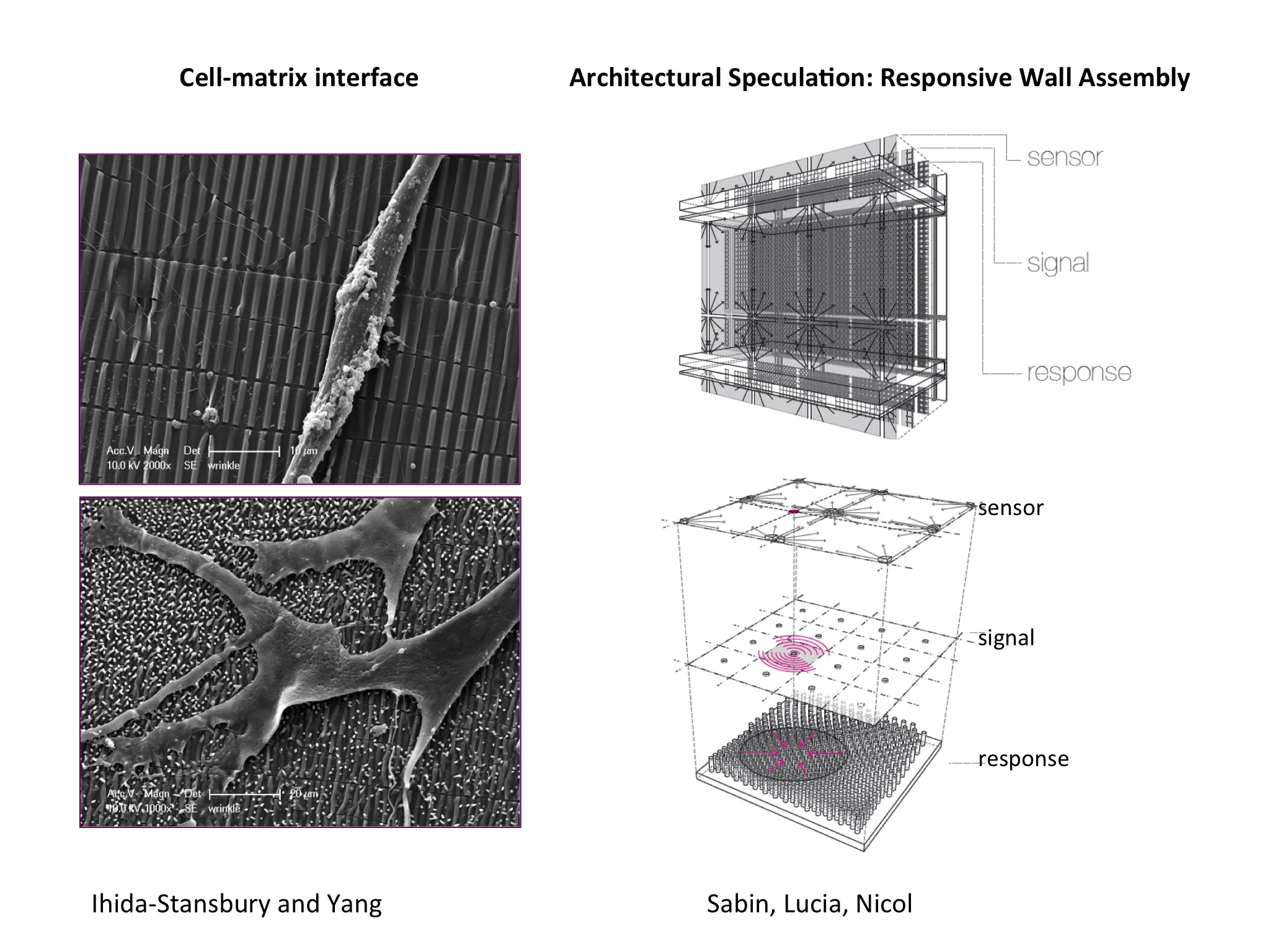

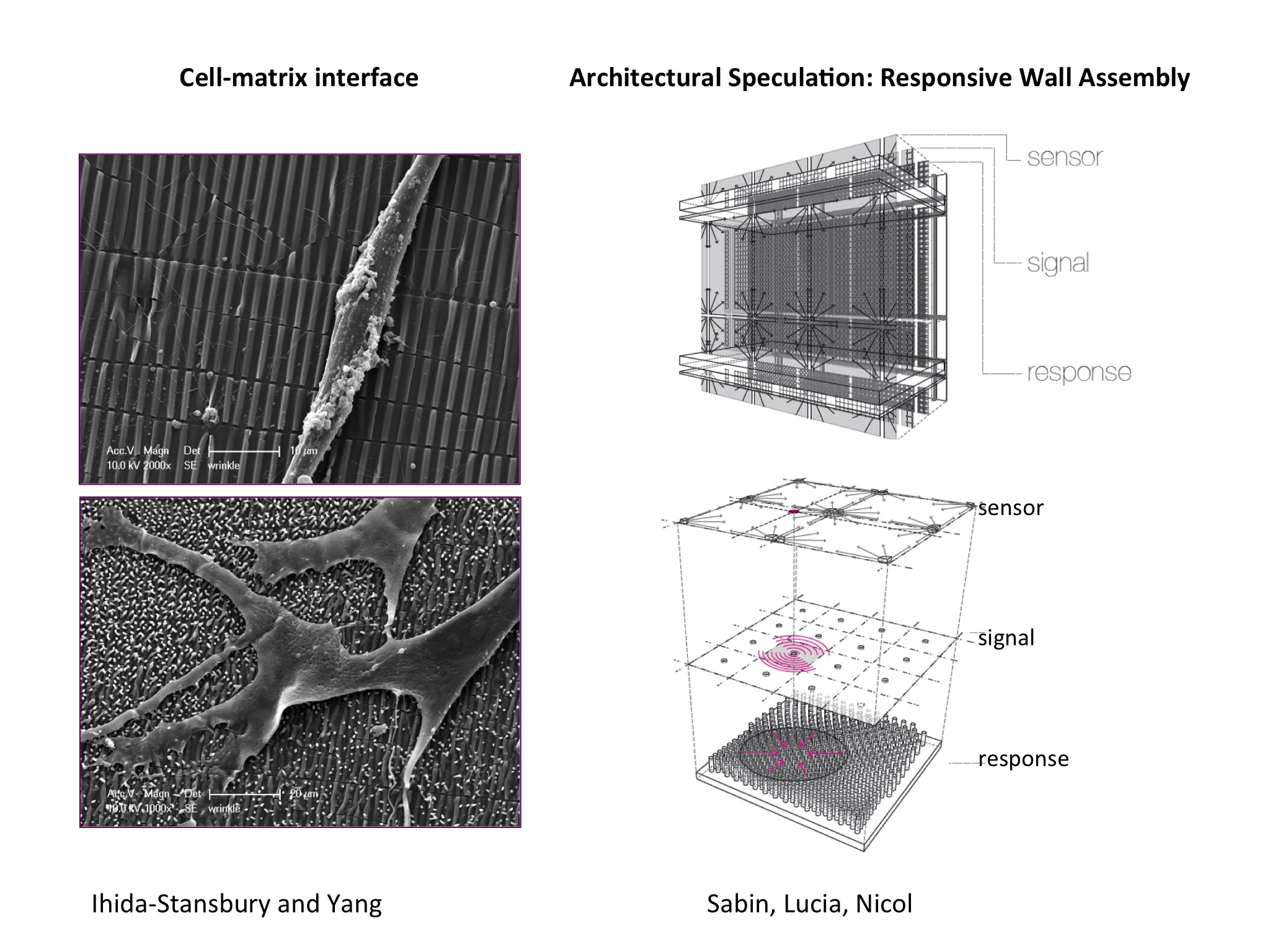

Figure 2 – eSkin project, sponsored by NSF EFRI SEED, UPenn & Cornell; our emphasis rests heavily upon the study of natural and artificial ecology and design, especially in observing how cells interacting with pre-designed geometric patterns alter these patterns to generate new surface effects.

Responsive architecture, a term first coined by Nicholas Negroponte, is a type of architecture that has the ability to alter its form in response to changing conditions, particularly at multiple scales. Popular examples include Galleria Hall West (Seoul, South Korea), Institut Du Monde Arabe, Aegis Hypo-Surface, POLA Ginza Building Façade, and SmartWrap™. Most of these examples, however, rely heavily upon the use of mechanically driven units that communicate through a mainframe, and they have to be nested within a building façade system. A building’s envelope must consider a number of important design parameters including degrees of transparency, overall aesthetics and performance against external conditions such as sunlight levels, ventilation and solar heat-gain. SmartWrap™ by Kieran Timberlake architects, integrates currently segregated functions of a conventional wall, and combines them into one advanced composite system. In contrast to these examples, our emphasis rests heavily upon the study of natural and artificial ecology and design, especially in observing how cells interacting with pre-designed geometric patterns alter these patterns to generate new surface effects. These tools and modes of design thinking, are then applied towards the design and engineering of passively responsive materials, and sensors and imagers.

The synergistic, bottom-up approach across diverse disciplines, including cell-matrix biology, materials science & engineering, electrical & systems engineering, and architecture brings about a new paradigm to construct intelligent and sustainable building skins that engage users at an aesthetic level with minimal energy consumption. We hope that our interdisciplinary work and modes of ecological design thinking not only redefine definitions of research and design, but will also address pressing topics in each of our fields concerning key social, environmental and technological issues that ultimately impact all humans in our built environments.

©Jenny Sabin 2013