by Frances Whitehead

“All that was ‘normal’ has now evaporated; we have entered postnormal times, the in-between period where old orthodoxies are dying, new ones have not yet emerged, and nothing really makes sense… We will have to imagine ourselves out of postnormal times—with an ethical compass and a broad spectrum of imaginations from the rich diversity of human cultures.”

– Ziauddin Sadar, Welcome to Postnormal Times, 2009

So prevalent are the terms “post” and “post-normal” as signifiers for the shifting ground of contemporary thought, that we must ask: “What is post-normal art?”

Thomas Kuhn’s term “paradigm shift” has entered the popular vocabulary, but recently we have seen a resurgence of interest in Kuhn’s thinking, including a reassessment of his ideas about “Normal Science” and the importance of “Post Normal Science”, especially to climate science and policy. Broadened still further by the economic events of 2008-09, the discourse around the “Post Normal” (or New Normal) is being addressed by thinkers from many sectors. The prefix “post” is frequently used to describe the current state of ecological, economic and social-cultural affairs, and implies that we are indeed living in the future of a past era. We invoke our past as part of our current paradigm –Post-carbon, Post-industrial and Post-colonial are inherited cultural landscapes. Interviews with a wide variety of such thinkers can be heard online at The Conversation: In Search of the New Normal.

Undoubtedly, Kuhn did not intend the term “Normal Science” to be understood ironically. However, in today’s usage, the idea of the “normal” functions as a trope, an ironic metaphor for the deep fissures and uncertainties in the cultural at large. Given the legacy of the avant garde and artistic experimentation, we sense this irony immediately when we transpose Kuhn’s model to Art practice. In this context, “normal” is an indictment of sorts, a failure to contend to what is all around us. We are faced with the curiously problematic proposition of “Normal Art” or the uncertainties and possibilities of “Post Normal Art.”

In the last few years, many artists have opted for the latter, shifting their creative practices away from “The Normal” towards a deeper engagement with systems, complexity, and context, a decidedly “Post-Normal” perspective. While some work with ecological themes of water, landscape, soil, food systems and remediative strategies, much of this new work connects ideas and sites in ways unimaginable a decade prior, bringing the art historically recognized genres of “earthwork”, “eco-art”, and environmental “activism” into connectivity with socio-cultural, rural and urban, art + design practices, principally through collaboration. Meanwhile, the global discourse in this area has adopted the theoretical framework of “sustainability” (even “Post-Sustainability with its focus on adaptation). These multifaceted perspectives see “Post” landscapes as actualizations of cultural paradigms and sites of intervention as Post Normal Art, connecting emerging critical, spatial and civic media and practices, further shifting the cultural quo.

Working through my collaborative studio identity ARTetal, my Post Normal practice has been focused primarily in urban sites. Emerging from the question, “What do Artists Know?” ARTetal has developed entrepreneurial strategies for artists to work at the urban scale and partner with equally adventurous civic partners.

SLOW Cleanup moves Post-Carbon environmental remediation into the territory of Post Normal Science as it engages the Chicago community and leverages underutilized capitals (assets) of space, time, and human capacity.

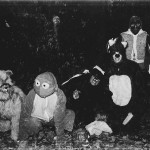

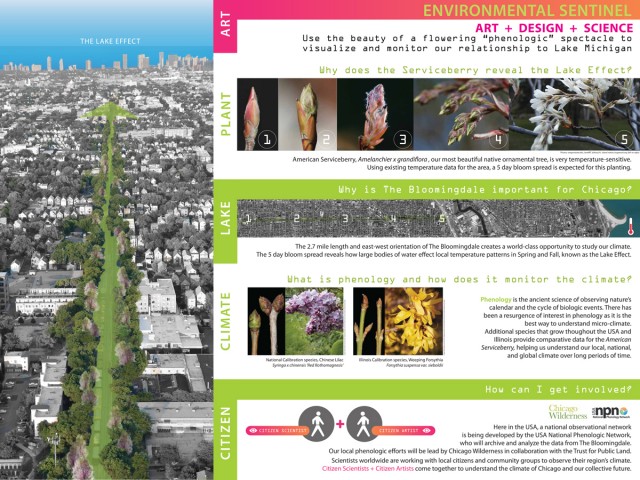

Environmental Sentinel is a three mile climate monitoring work planned for Chicago’s Bloomingdale Trail, a Post-Industrial adaptation project. Embedded within the landscape design, atop a repurposed railroad embankment, this phenologic planting will reveal the temperature moderating effect of Lake Michigan with a flowering spectacle, and signal micro-climate changes over the next century. The science will be conducted by citizen scientists and citizen artists, Post Normal “Art + Science”.

ARTetal Studio + The Bloomimgdale © 2012

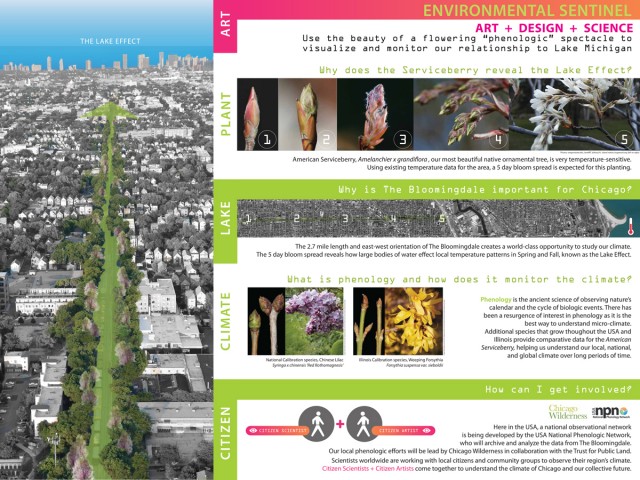

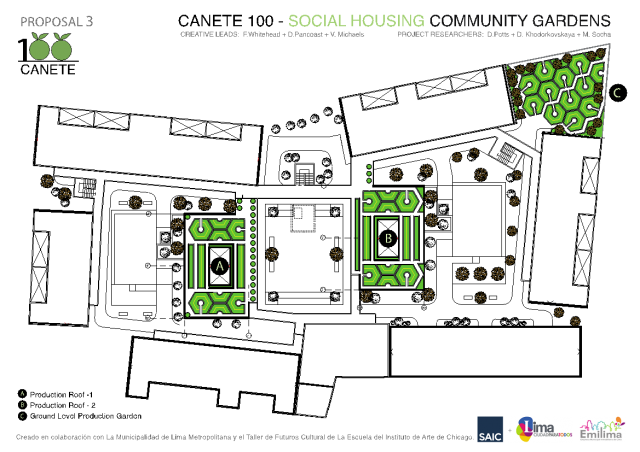

Understanding that communities of artists and designers are themselves under-utilized resources barely tapped, a Post Normal creative opportunity brings SAIC faculty and students to the service of the City of Lima, Peru with new urban agriculture programs. An open source response to Lima’s colonial legacy –a redistribution of capacity– this Post Colonial intervention is also Post Normal Cultural Heritage, as the site for the work is the Cercado, or historic district.

Spatially efficient hex-shaped growing modules for social housing rooftop garden, Lima Peru © The Lima Project 2012

Frances Whitehead © 2012

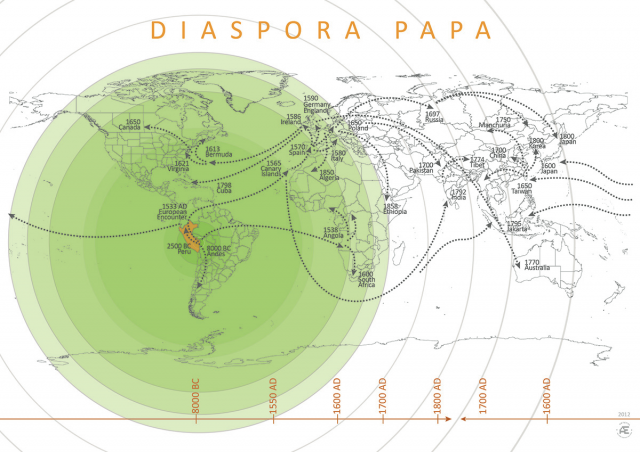

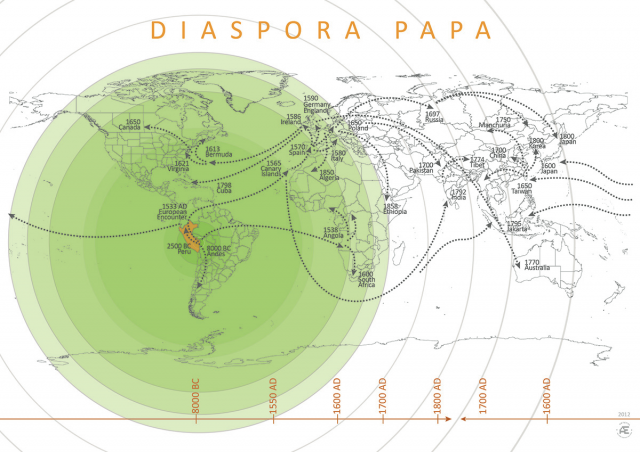

Introduced to the City of Lima through potato research at the Centro Internacional de la Papa, the global diaspora of the potato and its relationship to colonialism, tacit and explicit, connects these civically driven, urban interventions to the rural countryside of west Ireland and the Post Agricultural work of artist Deirdre O’Mahony.

Like many post industrial “shrinking” cities, the west of Ireland has steadily lost population from economic policy and emigration, leaving an abandoned landscape and shifting paradigms.

Deirdre O’Mahony Abandoned Clare The Shed School. Roxton County Clare, Ireland, © 2009.

O’Mahony frames her work in this way:

“The landscape of the west of Ireland has immense cultural importance, serving a double function as a representation of the post-colonial nation state and as a signifier of alterity in Ireland. My focus as an artist has been on reframing landscape as an active mode of cultural reflection, rather than a nostalgic reminder of a purer past“

Current (Post) rural development policies now promote the farmer as what O’Mahony refers to as “custodian of the landscape”, a paradigm shift from the rural as a site of food production to an arena of (Post Normal) cultural production. Here O’Mahony initiated and collaboratively runs the public art project X-PO; a “Post” post office.

O’Mahony describes the project:

“Re-imagined as “X-PO” the site is a functioning model of a reflexive space where the social, economic and environmental choices and problems of rural communities are visible and open for discussion. It is a space where different forms of knowledge: social, historical, agricultural and cultural, can make unexpected and transcendent connections and conjunctions. It also enables participants in a fragmented, dispersed social landscape to meet.”

Peter Rees X-PO Spring 2008, © Peter Rees 2008.

Much like policies in the US, European Agricultural subsidies have supported economically unsustainable small farms in the west of Ireland, paradoxically preserving much of the tacit, place-based, local knowledge around land cultivation. This knowledge is becoming increasingly redundant, forgotten, or outmoded in a “post- productivist” landscape.

Deirdre O’Mahony: SPUD © 2011

In this context O’Mahony has begun project SPUD, a pamphlet guide to making traditional Irish ‘lazy-beds’, a simple and effective way of cultivating potatoes that is also suitable for small urban gardens.

This inversion (or equation) of culture and agriculture, of post rural and post urban, of artist and agri+culturist, connects O’Mahony to urban sites through culturally driven knowledge transfer and the urban forager artist, Nancy Klehm. Both Deirdre O’Mahony and Nancy Klehm work with literal and metaphoric Shifting Ground by action research, a principal methodology of “Post Normal Art”.

Nancy Klehm ventures into the remote areas of cities such as Chicago, Detroit, and Los Angles, leading groups on foraging tours to discover and collect the comestibles of the post urban wilderness, replete with resilient species, native and non-native alike.

Writing under the moniker of Weedeater, Klehm brings decades of plant knowledge from her extended family of plantsmen and horticulturists to the service of what Klehm calls “homegrown counterculture”. Motivated by a fierce autonomy and deep respect for complex natural processes, Klehm hybridizes art practice with horticulture, direct experience, and deep community in equal measure.

Klehm explaining vermiculture at the Pacific Garden Mission greenhouse, 2008

Photo: F.Whitehead © 2008

Similar strategies are employed by urban arts groups such as Carbon Arts of Melbourne, Australia, and the rural development organization Littoral in the UK.

We can understand these projects as a constellation of diverse urban and rural practices, which utilize top down, bottom up and hybrid collaborative strategies and partnerships. In this way, Post Normal Art practitioners, including those cited here, work both within and outside of irony, both within and outside of experimental art models, and embrace the “chaos, contradiction, and complexity” that typifies life in Post Normal Times.

© Frances Whitehead 2013